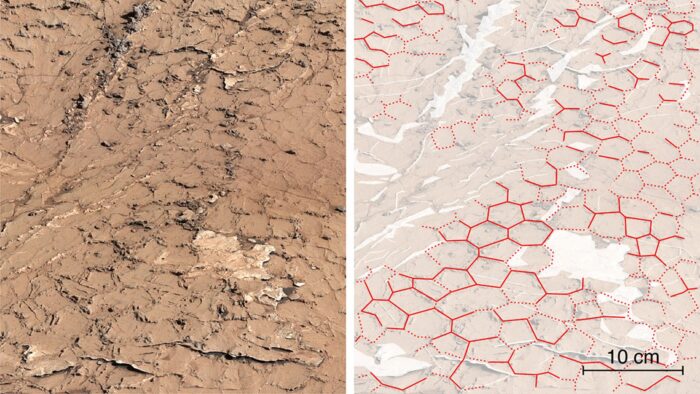

Mars, Mars, Mars ... Everyone in space exploration is a-buzz about missions to the Red Planet. In 2020, NASA is sending a rover mission—basically a super-cool dune buggy to travel the wild, sandy landscape and gather ground-level information about our planetary brother.

That as-yet-unnamed rover will join Opportunity and Curiosity, two similar vehicles already there. But that isn't the only company it will have. Also on board should be a first-time piece of tech for this planet: the Mars helicopter.

Get to the chopper!

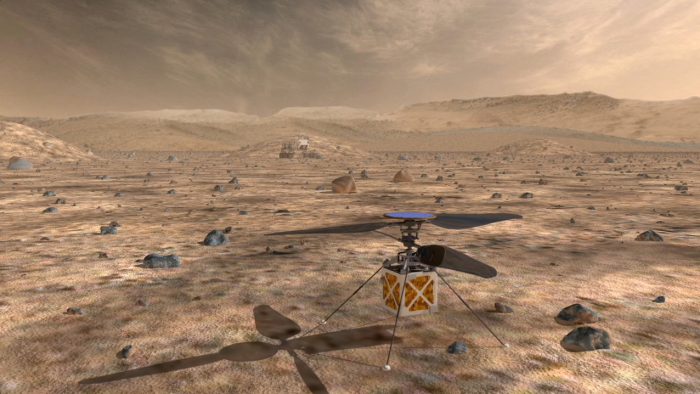

Will the Mars helicopter allow scientists to explore hard-to-reach features like Valles Marineris, the largest canyon in the solar system? We hope so! (Getty Embed)

This tiny chopper will be controlled by a combination of remote-control—all the way from Earth!—and will also be partly autonomous. It needs to be self-controlled to at least some degree. Instructions from Earth will take a few minutes to reach the chopper, which doesn't give its Earth pilot much chance to avoid that mountain in the way!

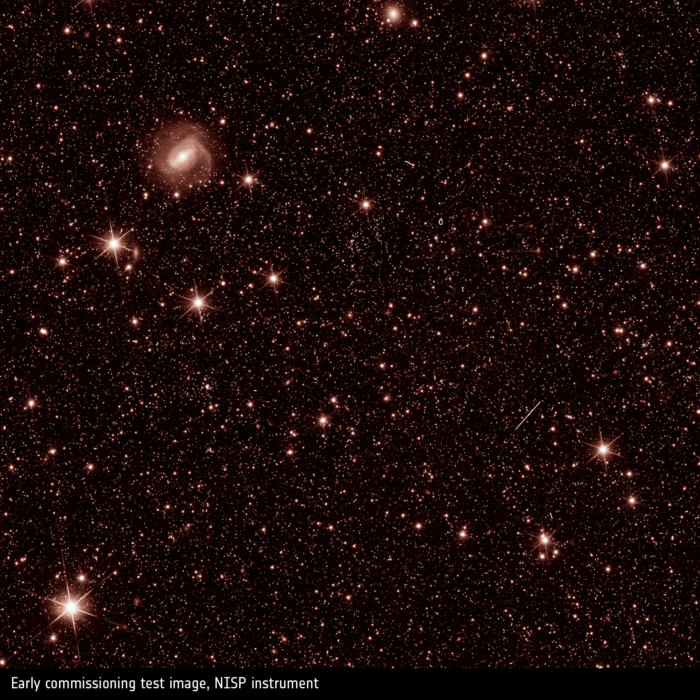

The Mars helicopter will give scientists an incredible chance to view and explore the planet as never before. Before this, they either had to rely on satellite images (which though accurate, are from miles above the surface) or on the cameras on the rovers (which are, of course, land-based). Think about how drone photography revolutionized how we're able to explore our own planet. If this experiment succeeds, we'll be able to do the same on Mars.

Super spinners

And why wouldn't it succeed? After all, Mars' gravity is weaker than ours, so flying should be a cinch, right? Well, the planet presents some unique challenges. Its atmosphere is a fraction of Earth's, and that's a real problem for flight. Whether it's a plane or a helicopter or a bird, flying things use the resistance of Earth's atmosphere to push against as they move through air. It's actually a lot like how swimmers use water—but since air is far less dense than water, flying things need to be lighter and/or use more power to be able to fly.

On Mars, the situation is the same only more so. This Mars helicopter is very light—just 1.8 kg. (four pounds).

(That's even lighter than this guy!)

Also, the blades must turn about 3,000 times a minute, which is about ten times the speed needed on Earth. Ultimately, the 2020-launched project won't reach Mars until February 2021. But to tide you over, check out the video below.

Contest alert

Don't miss the Science Odyssey Family Contest. Click HERE TO ENTER.

Science Odyssey is a 10-day, Canada-wide celebration of all things science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM).

Are you ready to meet the newest Mars explorer...? (NASA/JPL)

Are you ready to meet the newest Mars explorer...? (NASA/JPL)