New year, new ... space rock?

Our friends at NASA have a knack for celebrating milestone dates with new discoveries. In this case, they helped ring in 2019 with a fascinating space object. Ultima Thule!

What exactly is this curiously named celestial body? Is it really as fuzzy as it looks above? And why should we all be excited? Strap on your science caps, folks—a new year of learning has officially begun!

Wandering leftovers

At 12:33am EST on January 1, 2019 (which was just a half hour past midnight for those of us in cities like Montreal, Toronto, New York, and Boston), the New Horizons space probe flew past Ultima Thule.

RIGHT NOW, ~1 billion miles past Pluto, @NASANewHorizons is performing the most distant spacecraft flyby ever as it zooms past #UltimaThule, an icy, ancient rock in the Kuiper Belt. Watch live coverage: https://t.co/oJKHgKpQjH pic.twitter.com/U30yazzigo

— NASA (@NASA) January 1, 2019

This object is a 32 by 16 km (20 by 10 mile) asteroid that is located in the mysterious Kuiper belt. This distant region is found beyond the orbit of Neptune and is thought to be full of 'leftovers' from the birth of our solar system. It contains billions of objects orbiting our Sun—in fact, Pluto is a part of it!

But outside of Pluto and its moon Charon, we haven't gotten up close and personal with too many Kuiper belt bodies. And that's where Ultima Thule comes in. Formerly known as 2014 MU69, it is the most distant space object ever visited by a human-made spacecraft—a whopping 6.4 billion km (4 billon miles) from the Sun. Fittingly, Ultima Thule comes from a medieval term that meant "beyond the known world."

New Horizons, indeed!

Still analyzing

"Processing ... processing ... processing ..." (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

If the photo above leaves you less than impressed, take heart: this is not a final portrait. The data that NASA has received from New Horizons is still being received, and may take around 20 months to be fully poured over. In the end, NASA hopes to answer questions such as:

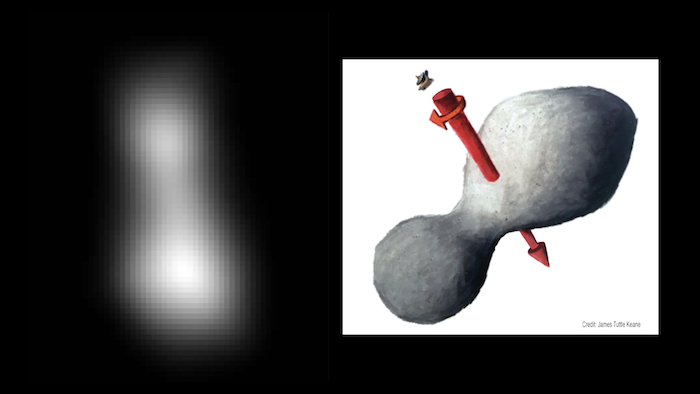

- Is it one bowling pin-shaped object, or two closely orbiting objects?

- In what direction does it rotate?

- How long does one rotation take?

- What is it made of?

- And ... what does that say about how our solar system formed?

In the end, that last question is the reason why New Horizons was first launched in 2006. Scientists want to know if the cosmic leftovers in the Kuiper belt can tell us something new about where we live.

Any predictions?

On the left is the first "up-close" image of Ultima Thule sent back by New Horizons. On the right is a sketch that suggests a possible shape and rotation of the asteroid. (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI; sketch courtesy of James Tuttle Keane)

On the left is the first "up-close" image of Ultima Thule sent back by New Horizons. On the right is a sketch that suggests a possible shape and rotation of the asteroid. (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI; sketch courtesy of James Tuttle Keane)