Though we write a lot about our solar system here, there's one place we don't discuss much at all.

Our closest planetary neighbour, Venus.

At first glance, this seems weird. Not only does Venus come nearer to us than any other planet, it's the most similar to us in size and composition, and sits within the so-called Goldilocks Zone—the orbital area that is the ideal distance from our Sun to support life.

What's more, a brand new study just released is claiming to have found traces of life in the clouds within Venus' atmosphere. Yes, life. So what in the world are we doing getting ready to send probes to distant icy moons like Europa and Enceladus when Venus is right here?

Before we get to the reasons why, let's look at what these claims of life are based on.

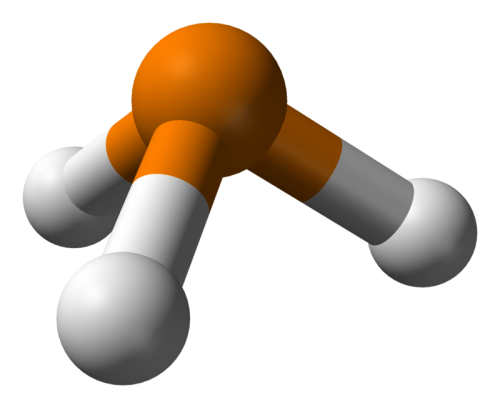

Phosphine dreams

Though toxic to us, phosphine is produced by some lifeforms. (Wikimedia Commons)

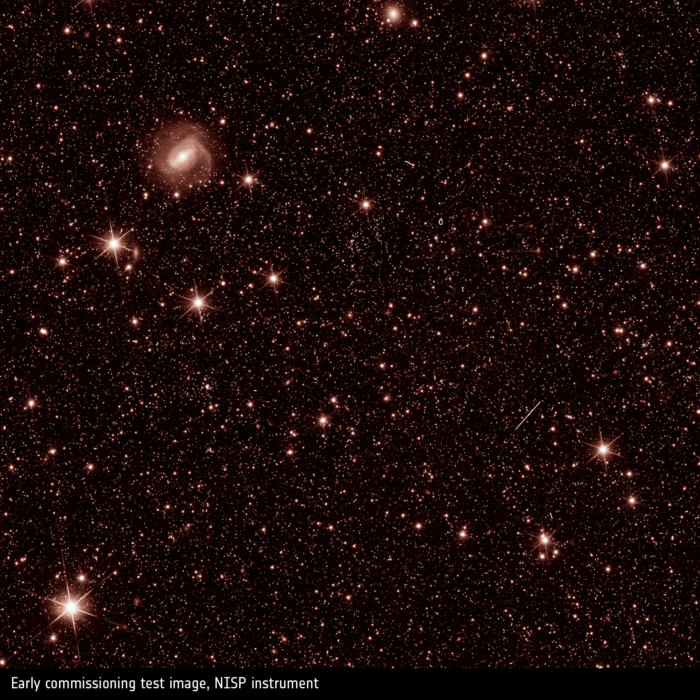

One of the biggest breakthroughs in astronomy was when scientists discovered that different elements and molecules absorb and emit light at different wavelengths. The basic idea is that these elements and compounds all have a unique wavelength signature or fingerprint—iron has one, so does helium, oxygen, and so on. Once you know what they are, you can use powerful telescopes to read these signatures and know what a star, nebula, or atmosphere is made of without ever visiting it.

Using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii, researchers investigated Venus' atmosphere and found evidence of a chemical called phosphine. Though phosphine exists in many places in the solar system, including on Earth, it generally has only two ways of being made. One is deep in the intense, mindboggling heat and pressure of the atmospheres on gas giants like Saturn and Jupiter. Here, phosphorus and hydrogen atoms are mashed together to form phosphine.

The other? It is made as a by-product of anaerobic life. These are primitive lifeforms that do not require oxygen for growth. On Earth, anaerobic life includes some bacteria, protozoans, and a few small fungi. So the question is, if phosphine is in the clouds on Venus... what is making it?

Furnace nightmares

The first-ever shot of Venus' surface, taken by Venera 9 in 1975, moments before it was destroyed by the planet's atmosphere. (Wikimedia Commons)

Perhaps another good question is, Why are we only finding out about this now?

During the 1960s and 70s, exploration of Venus was actually pretty common. The Soviet Venera and American Pioneer programs both sent many probes to orbit and, later on, land on the planet. But they quickly discovered something horrifying about Venus. It was a planetary pressure cooker.

It was entirely cloaked in dense clouds of carbon dioxide and sulphur. This thick and toxic atmosphere rained storms of acid, trapped so much solar energy that the ground burned at 425°C (800°F), and generated as much pressure at the planet's surface as we would feel being 900 metres (3,000 feet) deep in the ocean. In other words, any probe we sent there would be corroded, fried, and crushed almost immediately.

Even the best efforts of Soviet scientists allowed the Venera 13 probe to last just 127 minutes before being destroyed by Venus' hostile environment. Meanwhile, Martian rovers like Opportunity and Curiosity are able to wander Mars for a decade or more.

If a heavily shielded robot made of metal couldn't even last long enough on Venus to watch one Lord Of The Rings movie, what hope would life ever have of existing there?

Time to go back

That was pretty much the thinking. By the end of the 1970s, exploring Venus looked like a dead end and astronomers focused most of their attention on Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the rest of our solar neighbourhood. This obviously paid off, too. But now with this latest discovery, many people—including the director of NASA—are saying it's time to go back to our twin planet.

Life on Venus? The discovery of phosphine, a byproduct of anaerobic biology, is the most significant development yet in building the case for life off Earth. About 10 years ago NASA discovered microbial life at 120,000ft in Earth’s upper atmosphere. It’s time to prioritize Venus. https://t.co/hm8TOEQ9es

— Jim Bridenstine (@JimBridenstine) September 14, 2020

Finding phosphine is not a life-finding slam dunk, of course. But as Bridenstine points out in his tweet, part of the search for extraterrestrial life is accepting that we'll probably be surprised by where it exists. Like high in our own atmosphere!

On the surface, Venus today is a monstrously awful place. But in its past? Most scientists believe that it was covered in water, with a hospitable atmosphere and a very comfortable temperature. It may have once been a better place to live—and more lively—than Earth was. Why wouldn't some form of life have found a way to hang on?

Thanks to this study, we may finally be on the way to answering that question for certain.

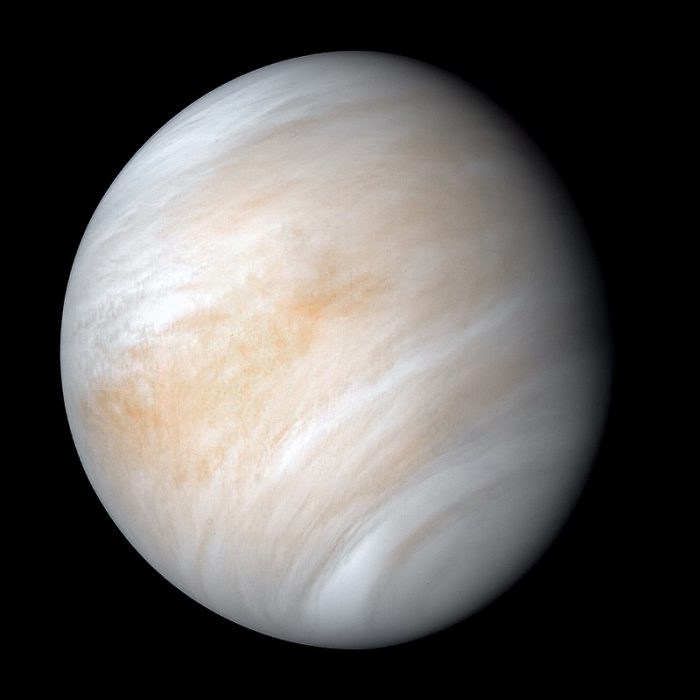

It was once felt that Venus' dense clouds made it unliveable. Now, a study claims that life is actually in the clouds themselves. (NASA)

It was once felt that Venus' dense clouds made it unliveable. Now, a study claims that life is actually in the clouds themselves. (NASA)