When it comes to space, everyone is talking about Mars. And why not?

What could be more exciting for an astronaut than walking on a whole other planet? It's pretty darn neat, we agree. But lost in all of this Martian mania is a very simple fact.

Mars is not home. And it would not welcome humans with open arms.

No, we're not saying that there are aliens there waiting to defend their turf. Rather, it is the planet itself that would make any visit a perilous one. With an atmosphere less than 1 percent the density of Earth's, freezing temperatures, and nothing remotely breathable, Mars is one hostile spot. For any visit to be successful, we need to maximize whatever resources that we can find there.

And that includes water.

Scientists have already discovered reserves of water ice in the polar caps. But now a new study has found evidence of water buried below the surface at the base of the Valles Marineris, a.k.a. the largest canyon system in our solar system (it's basically the length of the entire continental United States!).

How do they know this? And how might buried water be of help to humans?

Let's dig in!

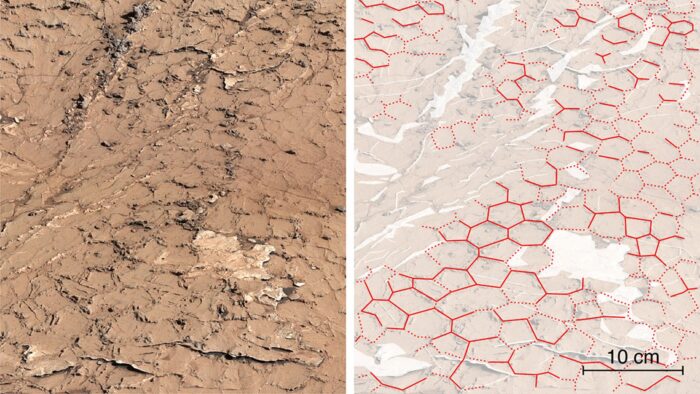

Martian permafrost

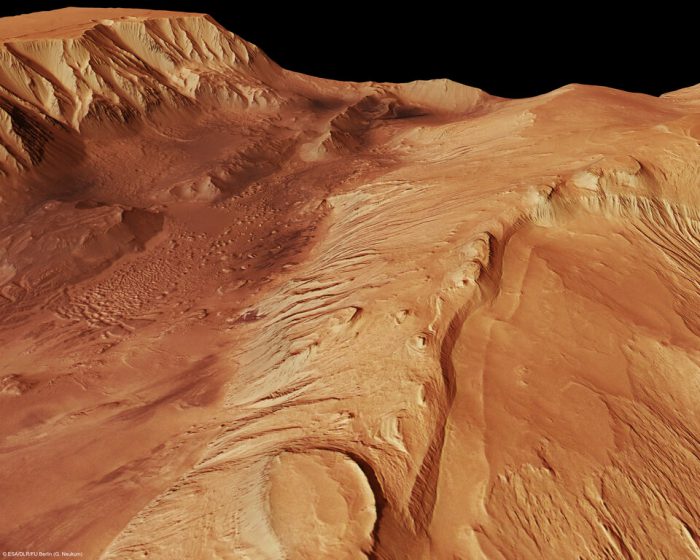

A close-up model of the Candor Chasma, a section of the Valles Marineris where it is believed that water is stored underground. (ESA)

If there is water in Valles Marineris, it is likely trapped as permafrost. This is when water and soil are frozen together into an ice-like solid. (By the way, for more on permafrost here on Earth, OWL magazine readers can look at our December 2021 Insider feature on it!) The water could also be there as an underground layer of pure water ice—like sheet of icing in a cake!

Either way, it's definitely not sitting there on the surface. So how do scientists know about it? Well, you see, they've got this friend...

FREND-ly advice

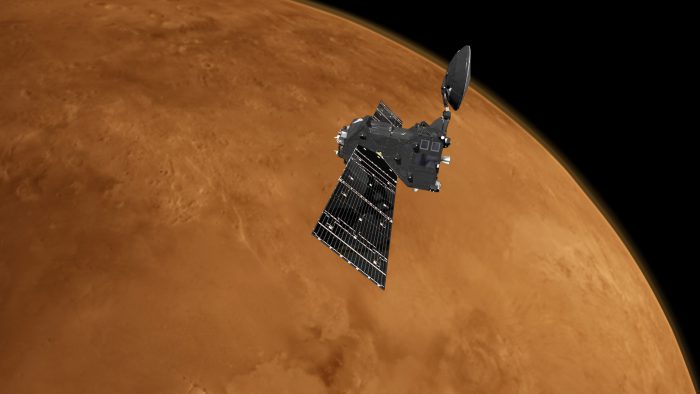

An artist's impression of the Trace Gas Orbiter above Mars. This is the satellite that made this discovery. (ESA)

Pardon us: that's actually FREND, or Fine Resolution Epithermal Neutron Detector. This device is located onboard the ESA-Roscosmos ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO). (Hmm, these names aren't getting any less complex, are they?)

In short? The TGO is a satellite launched by a joint effort of the European and Russian space agencies. The FREND device reads levels of hydrogen and neutrons in the planet's soil. "With the Trace Gas Orbiter," says Russian physicist Igor Mitrofanov, "we can look down to one meter below this dusty layer and see what's really going on below Mars's surface."

Basically, drier soil emits—or releases—more neutrons than wetter soil. So when the readings came back for some of the soil along the bottom of the Valles Marineris, scientists became really excited!

What might it mean?

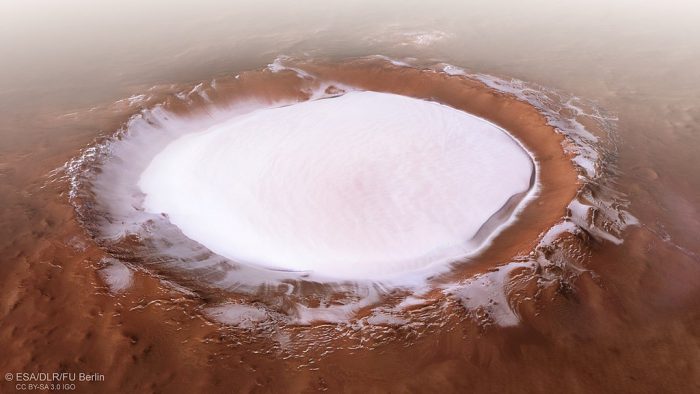

Mars does have plenty of surface water ice, but it is near the poles. On such place is the Korolev Crater. This new discovery is exciting because the Valles Marineris is at the equator where temperatures are warmer (though still very cold by Earth standards). (Wikimedia Commons)

There are a couple of reasons to be thrilled about these findings. For starters, this could be a source of water for humans when missions are sent to Mars. For those missions to work, astronauts will need to have some local source of water on the planet. It is simply too heavy to transport in large amounts all the way from Earth to Mars.

Secondly, if there really is permafrost on Mars, it would be well worth digging up and examining. Because if life ever existed on Mars, it would've been connected to water, and there's a good chance it is frozen in permafrost. The same is true here on Earth, where more and more fossils and preserved remains of ancient life are being found in thawing permafrost every year.

A source of water? Martian fossils? It certainly sounds like we're going to visit Valles Marineris some day, doesn't it?

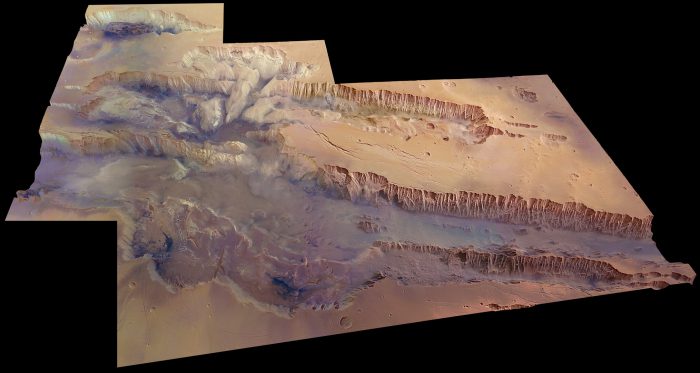

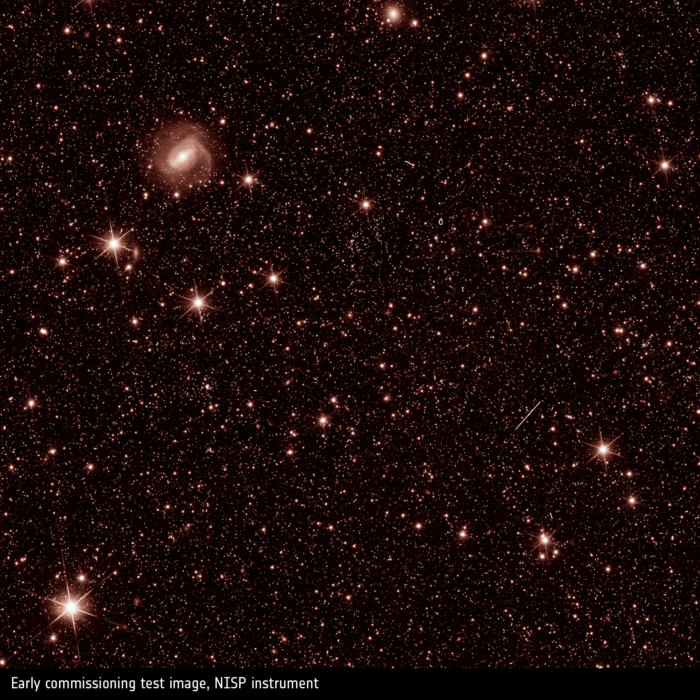

The collection of photos showing the enormous Valles Marineris system. (ESA)

The collection of photos showing the enormous Valles Marineris system. (ESA)

😀