A new study claims to have discovered how tiny tardigrades are able to survive being completely dried out. Even if it is decades before water arrives to return them back to normal.

Their cells are protected by a unique type of proteins that provide a remarkable defense against this threat. And now scientists are curious about whether or not these same proteins could be used for a variety of other uses. Even to help strengthen human cells in stressful environments like outer space and other worlds!

Wait, why are tardigrades so special?

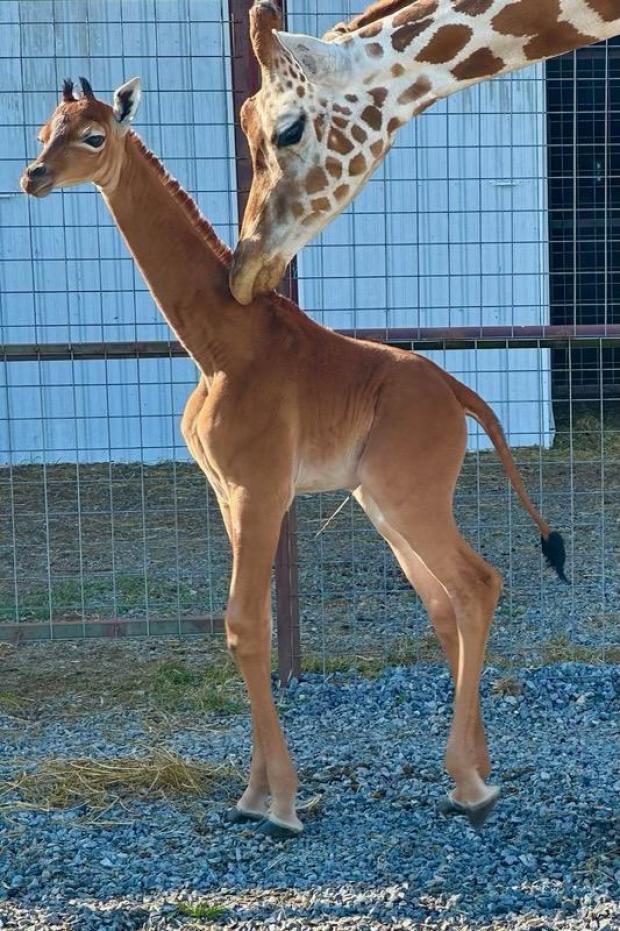

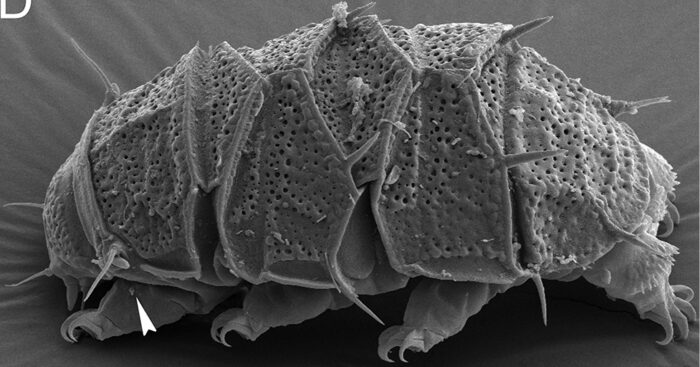

An electron microscope image of a tardigrade. (Wikimedia Commons)

And what are they? Fair questions!

Also known as water bears and moss piglets, tardigrades are adorable microscopic creatures that are only about half a millimeter (0.02 inches) long. They are shaped like a grain of rice, have eight legs, and a snout like the end of a hungry toothpaste tube.

They are also the most indestructible creatures known to humans. Seriously.

They've been boiled, frozen, crushed, fired from a gun, left in outer space, subjected to massive radiation, and somehow they always manage to survive. And thrive!

They can even be dried out to the point where 99 percent of the water leaves their body. Instead of dying (as any other animal would), they turn into an inanimate (motionless) object called a tun. (This state is also known as anabiosis.)

But as soon as water returns, they plump back up like a ramen noodle and squiggle back to life!

How do they do it?

This ability has fascinated scientists for a long time. Whether in water or on land, all living things are filled with water. (Humans are over 70 percent water). It is vital to life as we know it.

Normally, when a living cell dries out, its walls collapse and lose their structure. They basically fall into themselves. That's a big reason why a dried out (or desiccated) animal can't be brought back to life by simply returning water to its body. The cells are too damaged.

But miraculously, tardigrade cells don't lose their structure. The reason is a series of proteins called cytoplasmic-abundant heat soluble (CAHS) proteins. (A protein is a complex molecule that is crucial to living things.) As the water disappears, the proteins get to work. They create a spiderweb network structure that reinforces the cell wall.

According to University of Tokyo biologist Takekazu Kunieda, who helped run the study, these CAHS are unique to tardigrades and "are responsible for protecting their cells against dehydration."

Amazing!

What might this mean?

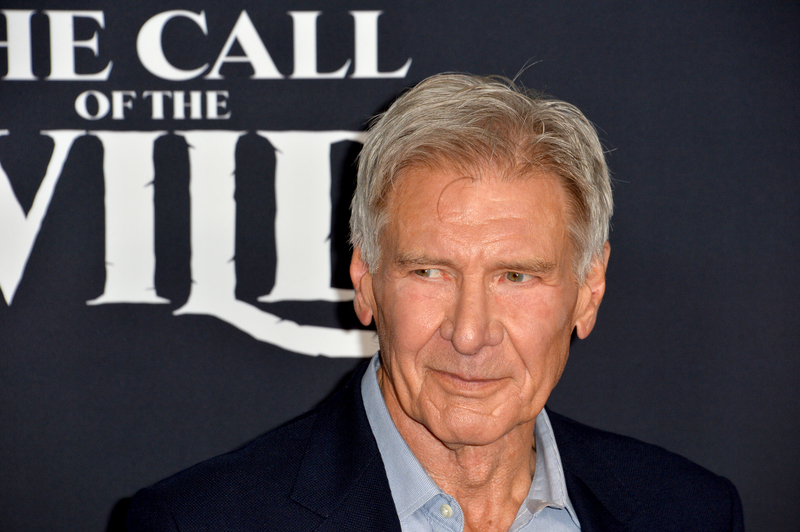

Will astronauts of the future use tardigrade proteins to help them survive better in space? (Getty Embed)

These proteins are obviously special to tardigrades. But can they also help us? Maybe!

Tests in the same study that used CAHS with human and insect cells found that the proteins also increased the stiffness and resilience in those cells when they lost water. No one is saying that these proteins could help a human survive for decades in a dried-out state like a tardigrade can (Gross!).

But they could help humans be more resistant to some of the severe conditions of space travel, like microgravity and radiation. These are some of the biggest challenges to overcome when spending long periods in space or on other worlds, like Mars.

And there are other possibilities, too. Take human blood. Hospitals constantly need people to donate blood because it only lasts in a fridge for a few months. But biologists like Thomas Boothby of the University of North Carolina believe that the secrets inside tardigrade biology could be used to make dried human blood. This could last on a shelf for years, and be ready to use (and save someone's life) in an instant—just add water!

Whatever the future holds, it is very possible that one of the world's smallest known creatures could end up having an enormous impact.

This is an image of a tardigrade that has been magnified 40 times its normal size. (ID 157748743 © Ivanmattioli | Dreamstime.com)

This is an image of a tardigrade that has been magnified 40 times its normal size. (ID 157748743 © Ivanmattioli | Dreamstime.com)