The Juno spacecraft has given astronomers—and the public— an chance to view Jupiter like never before.

Since its arrival in 2016, it has been collecting a vast amount of data on the world. One of the most revealing things it has shown us are images of the many, many storms across the huge planet. As a gas giant, Jupiter is essentially an enormous and dense network of clouds, all held together by a powerful gravity.

But Juno has given us more than just images of these storms. It has also collected years worth of data on something special that happens inside these storms.

Lightning!

Though we've known about lightning on Jupiter going back to the Voyager probes in the 1970s, Juno has collected data about these strikes in far greater detail than ever before—down to the millisecond of how it grows and moves. And according to this data, Jupiter lightning is actually quite similar to what we have on Earth!

Step by step

Lightning over Earth. Every 'bolt' of lightning is made up of a series of rapidly occurring 'steps'. (Photo 179692922 / Lightning © John Sirlin | Dreamstime.com)

Lightning may appear to be one solid beam of electricity, but it actually happens in what scientists refer to as steps.

The process is started by a series of collisions inside a thundercloud. Upward winds inside the cloud carry water droplets from the bottom of the cloud to the top, where they freeze. At the same time, downward winds carry tiny pieces of ice back down to the bottom of the cloud. These water droplets and ice pieces collide over and over, generating tremendous amounts of electrical energy inside the cloud.

Eventually, this energy is released as lightning. And the lightning builds in stages, or steps, each one being several hundreds to thousands of metres in length. Of course, these steps occur so fast, that to our eyes the lightning appears to happen all at once.

Similar but different

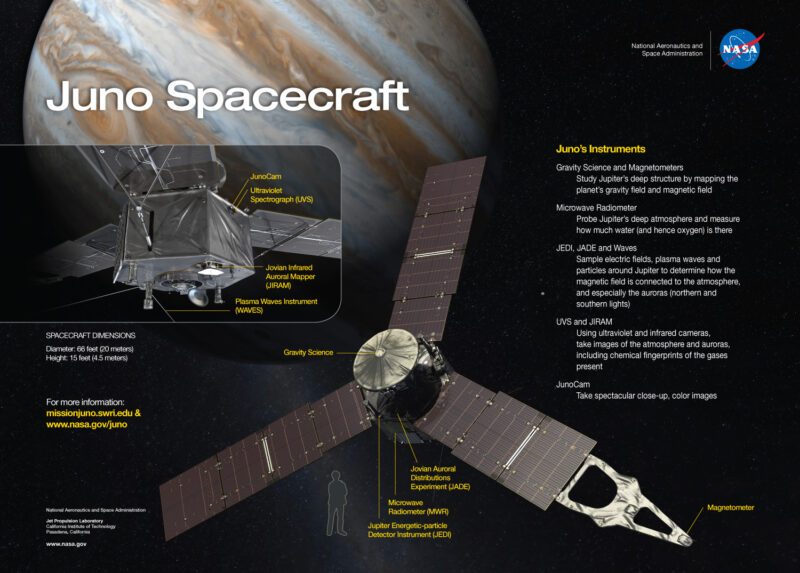

Juno is equipped with several sensitive instruments for examining Jupiter and its moons. Its microwave radio meter is what has allowed scientists to learn more about the planet's lightning. (NASA)

Jupiter is covered by a thick blanket of ammonia clouds, but underneath that are also clouds of water, much like what we have on Earth. And thanks to painstaking analysis of the data collected by Juno, researchers have been able to confirm that lightning in these clouds happens in the same stepped way as on Earth. Neat! But how did it do this?

Juno was able to collect this data not with photos but with a super sensitive instrument that reads radio wave emissions. Lightning releases radio waves as it happens. This allowed Juno to track the stages of how lightning developed—researchers were really struck by the similarities between there and Earth.

Of course, Jupiter and Earth lightning is still not identical.

For one, our lightning storms are far more concentrated around the tropical regions of the planet. But on Jupiter, lightning happens more closer to the polar areas. And also more in the northern hemisphere of the planet.

Why? That's a good question! One that scientists will be poring over as they continue working on better understanding the planets in our solar neighbourhood.

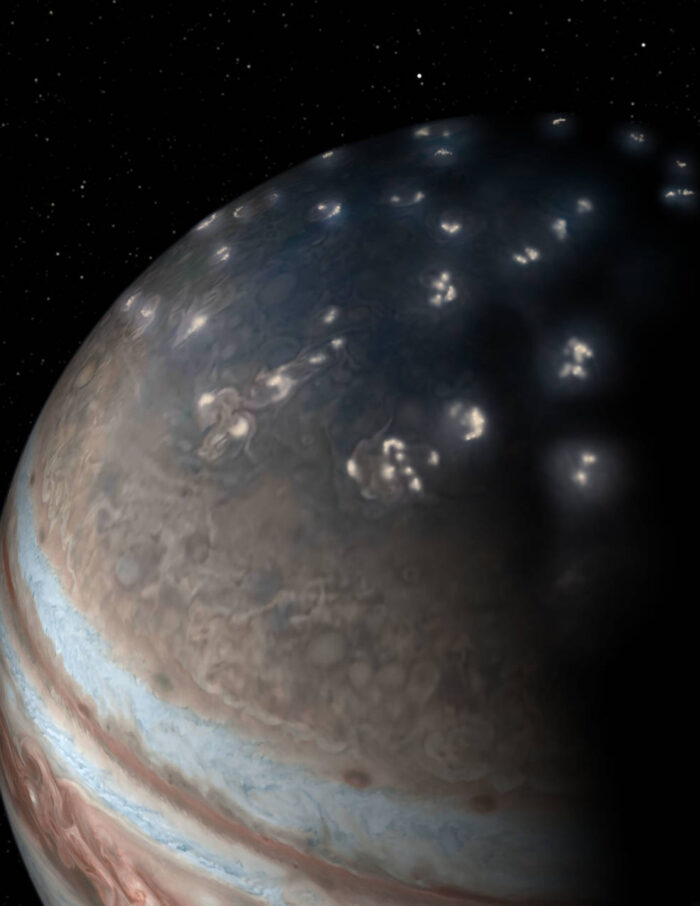

Pretty! A 2018 image of lightning storms across northern Jupiter taken by Juno. (NASA/JPL-CalTech)

Pretty! A 2018 image of lightning storms across northern Jupiter taken by Juno. (NASA/JPL-CalTech)

I love Jupiter 😀 😀 😀 😀