When it comes to the 5,000-year-old monument known as Stonehenge, the questions are endless.

How was it built? (Research suggests that many of the stones were dragged from sites hundreds of miles away, all before even the invention of the wheel reached this part of the world.)

Who built it? (It is difficult to narrow down the culture—or cultures—that built it because no written records exist.)

And then there's maybe most interesting question of all. Why was Stonehenge built at all?

For years, scientists have noticed that the placement of the stone lines up perfectly with the position of the Sun during the summer and winter solstice. (These are longest and shortest days of the year—they are key dates in many ancient cultures around the world.)

And now a new study from researchers at the University of Salford in Manchester, England suggests that it was also designed to amplify voices and music during ceremonies and rituals. It this is true, it would have been a major achievement in acoustics—one that was many centuries ahead of the curve.

What is acoustics?

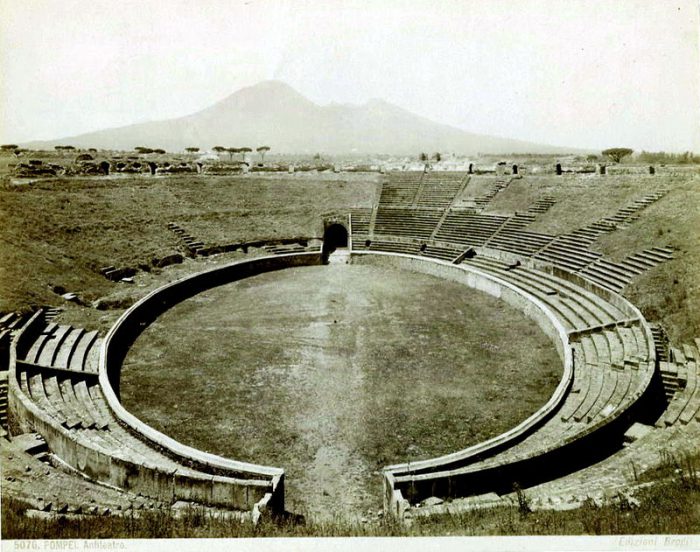

The Amphitheatre of Pompeii was built by the Ancient Romans in about 70 BC. (Wikimedia Commons)

Acoustics is the study of how sound is transmitted, especially in a room, building, or semi-enclosed space. It explains why your voice seems louder and echoes in an empty, tiled room, like a shower (the sound bounces off of those flat, reflective surfaces). And it is also explains why your voice sounds 'deader' in a room full of carpet, pillows, and stuffies (all of those padded surfaces and objects absorb sound).

Humans have known about acoustics for a long time. It's what allowed ancient civilizations like the Greeks and Romans to build huge theatres to amplify the voices of people on stage for a large audience. They did this with curved, sloped structures—and sometimes roofs—that channeled, focused, and reflected sound waves.

But even the Greeks were only doing this 2,500 to 3,000 years ago. Meanwhile, Stonehenge was built about 2,000 years before that. How good a job did the ancient monument do of amplifying sound? That's exactly what this new study wanted to find out!

Making a model

"Testing! Testing!" Acoustical engineer Trevor Cox tests the Stonehenge model at the University of Salford. (Acoustics Research Centre/University of Salford, Manchester)

Today, Stonehenge doesn't look as it did in the past. And it also took centuries to complete, meaning that its look changed through history. But archeological research has given historians a picture of what it looked like at its peak, 4,500 years ago.

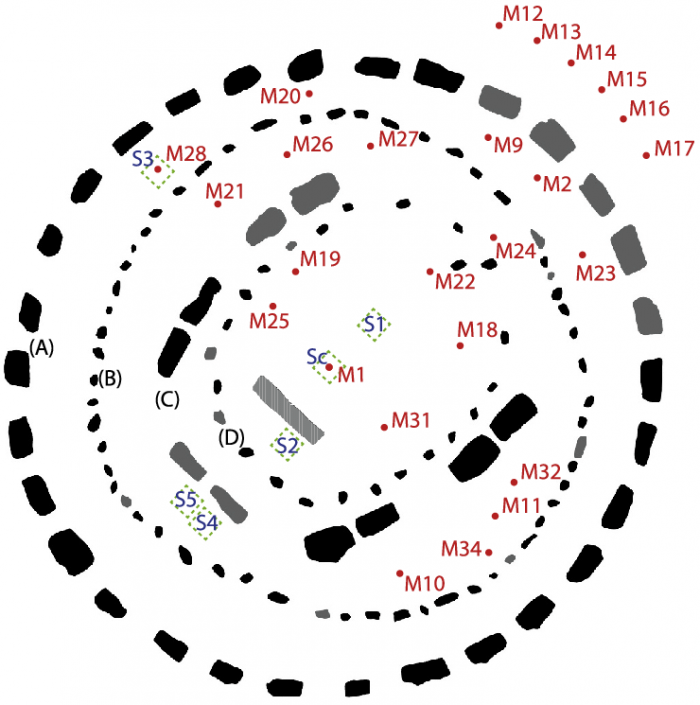

Researchers at the University of Salford in Manchester used this information to build a scale model of Stonehenge. This means that the model is the exact same proportions as the real thing, just smaller (in this case, 12 times smaller). They placed the model inside a soundproof studio that is designed to be as 'dead' as possible (no echoes).

And then they ran tests. They played recordings of voices and music in certain parts of the model—microphones placed around the model recorded how it sounded in different areas.

What the study found

This plan shows where different microphones (M) and speakers (S) were placed to test the model. (Acoustics Research Centre/University of Salford, Manchester)

Even without a roof to trap sound waves, sounds from the centre of the model significantly increased in volume inside the outer stone circle. Even more interesting? Anyone standing outside the stone circle would've barely been able to hear the sounds at all. And outside sounds would not have been heard inside the circle.

Stonehenge both increased volume and added a layer of privacy and quiet (something very similar to what is now called 'soundproofing').

Did the ancient civilizations that built Stonehenge know that they were doing this? Or was it all just a happy accident that came with a design built to celebrate solstices? Whatever the truth, it just adds to the mystery—and genius—behind this artifact.

Stonehenge as it apeears today. (Photo

Stonehenge as it apeears today. (Photo

Cool!

That’s awesome!

OMG thats soooooooooooooo cool