So, let's say you're a paleontologist. After decades of research and debate, one of the greatest mysteries of both prehistoric and current life has been solved.

Birds are the descendants of dinosaurs.

The chicken, the wren, the blue jay, the albatross, even the penguin and the emu ... they can trace their evolution hundreds of millions of years back to theropods like Compsognathus, Velociraptor, and, yes, even the mighty Tyrannosaurus rex.

So your work is done here, right?

No way!

Because even if we know that dinos and birds are connected, there's still the matter of when this transition actually began happening. What was the species that sat in between these creatures being a predator that crept and stalked the land to one that was capable of flight?

Where did wings come from?

There's not likely any one true 'missing link'—an animal that directly connects the evolution of the one group to the other. But new research from the University of Tokyo is giving us clues on what to look for as we search.

And that thing is something called the propatagium.

Finding the invisible

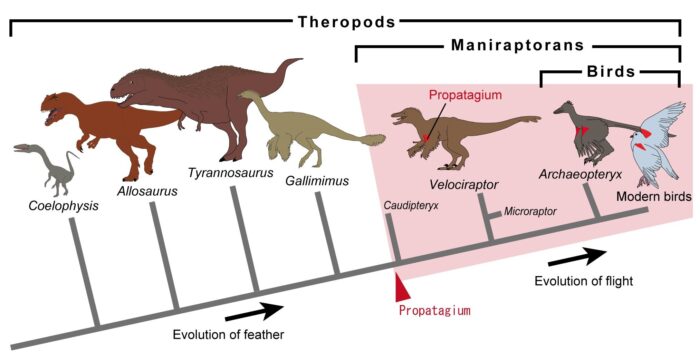

This chart shows a variety of theropods leading up to the modern birds. Some of the theropods, especially the large ones, didn't have the membrane. But researchers believe many later theropods did have them. (Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa, Zoological Letters, 2023)

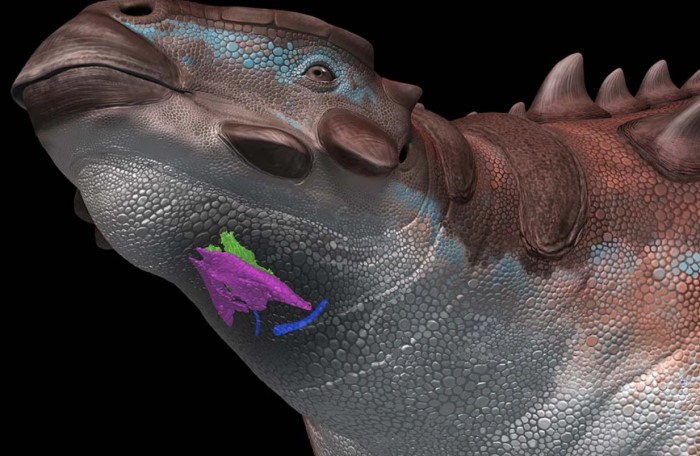

The propatagium is a membrane that is the common bond between the wings of all flying vertebrates, such as birds and bats. If you had one, it would be created by a tendon (an elastic fibrous tissue) connecting your shoulder to your wrist. No wonder flapping our arms doesn't work!

Without this membrane, the birds' forelimbs (wings) would be less connected as one, and would have less strength as they flap. And therefore, no flight.

In fact, researchers have found that not only are flying (and some gliding animals) the only vertebrates with a propatagium, but the membrane has either disappeared or lost its usefulness in flightless birds.

So if we're looking to see where wings have come from, we should simply look for fossils of dinosaurs with a propatagium. Easy peasy, right? Except ...

The stuff that the propatagium is made of—tendons and membranes—are soft tissues. And this stuff, like muscle, skin, hairs, fur, and cartilage, almost never gets fossilized. (Though there are some dinosaur fossils with soft tissue, they are tremendously rare.)

Instead, it decays and disappears completely. And while some thicker tendons can leave behind a scar, or mark, on the area of the bone where they attach, the tendon in the propatagium is very thin.

So how do you find evidence of something on a fossil that disappears without leaving behind any physical trace?

Strike the pose

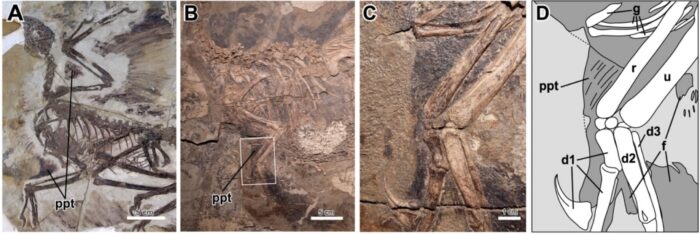

These photos show fossils of theropods with forelimbs in flexion (or bent). A) is a microraptor, B) is a Caudipteryx. C) and D) are enlargements of the forelimbs in B). (Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa, Zoological Letters, 2023)

The solution to this problem, according to researchers at the University of Tokyo, is to look for a signature arm pose in the fossil.

When birds die, the bones in their wings are stuck in something called flexion. This essentially means that they are flexed, as though you were curling your arms to show off your biceps! The reason they are in this pose? The propatagium holds them there.

So if a theropod dinosaur had evolved to have a propatagium, then when it died, it would also have both of its forelimbs in flexion. And while an animal without this membrane can possibly be fossilized with its arms in the same position, arms in flexion would be an exceptional indication that the magic membrane was present.

Already, the researchers behind this study believe that many theropods that have already been discovered, such Velociraptors, had an early version of a propatagium. This means that even though those creatures couldn't fly, they were well on their way to evolving into animals that could.

Now that's a study that can really take flight!

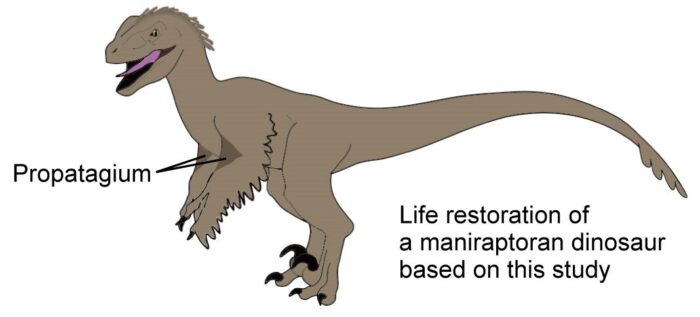

New researchers is suggesting ways to discover whether theropods like maniraptorans had a membrane found in all flying birds today. (Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa, Zoological Letters, 2023)

New researchers is suggesting ways to discover whether theropods like maniraptorans had a membrane found in all flying birds today. (Yurika Uno and Tatsuya Hirasawa, Zoological Letters, 2023)