A dinosaur 'mummy'—a fossil that is so well preserved that parts of its soft tissue, such as skin, flesh, organs, or feathers, remain—are very rare.

This is because after an animal dies, these are the things that decompose first. And they decompose quite rapidly, too. All that is left behind are the bones. That's why dino exhibits look the way they do. A bunch of skeletons!

The only way for a dinosaur mummy to be made was for the body to be buried by a natural event extremely soon after the animal died. Or so we thought.

But now, new research into a partial mummy named Dakota has revealed that over ways are possible. And they may be more common that we realize!

How did we think mummies were made?

An Edmontosaurus skeleton as we usually see them. (Getty Embed)

Before we get into Dakota's curious case, let's look closer at how paleontologists first believed dinosaur mummies were made.

For decomposition to start, oxygen is needed. That is why we vacuum-seal certain perishable foods when we store them in the fridge. This keeps oxygen away from the food, allow it to stay preserved.

While there is no vacuum sealing machine in the wild, we do have certain catastrophic events that can quickly bury an animal. These include flash floods and landslides. There are also some conditions, such as bogs and swamps, where the water is so full of mosses and dead plant material that it acts similarly to mud and sediment.

In these cases, the body is quickly sealed away from oxygen, giving soft tissues the chance to be preserved. This method works very well and is how we got the famous Nodosaurus mummy, one of the most astonishing dinosaur fossils ever found.

But there is another way, too ...

Who is Dakota?

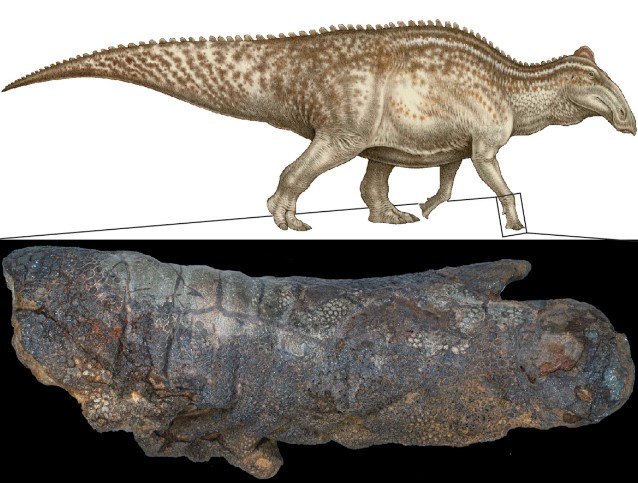

An illustration of how Dakota would've looked when it was alive, and, at the bottom, its amazingly well-preserved foot. (Natee Puttapipat/Creative Commons)

Dakota is an Edmontosaurus fossil that was discovered in Hell Creek in North Dakota (this is an area that is famous for its plentiful fossils from the Cretaceous Period). The 67-million-year-old remains were first found back in 1999. The prize piece? A section of exquisitely preserved dinosaur skin, so packed with iron that it gently glitters under light!

In 2014, the skin was put on display to the public at the North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum in Bismarck (North Dakota's capital). Meanwhile, the rest of the fossil remained encased in rock. As paleontologists freed more and more of the bones, they found all sorts of clues to what happened to the animal after it had died.

Very important clues!

A scavenger's meal

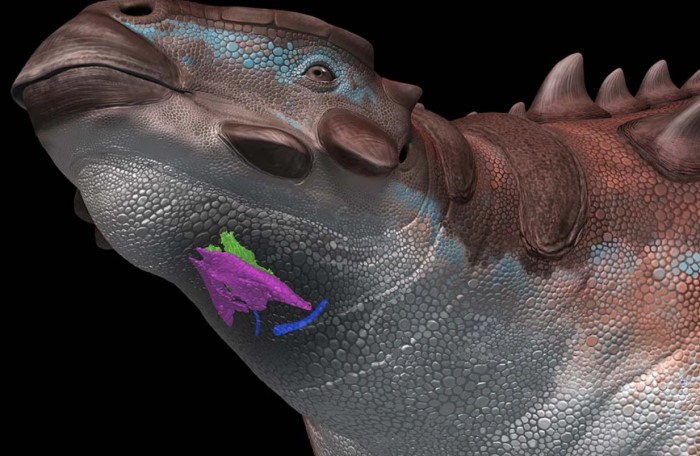

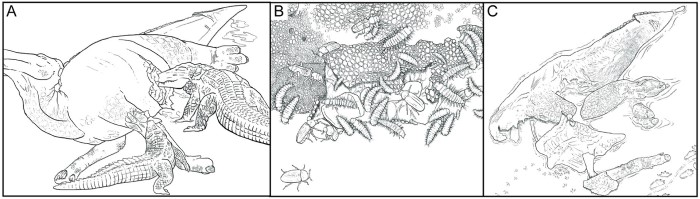

An illustration of how paleontologists believe Dakota was preserved. A) Large predators and B) insects and smaller creatures fed on the carcass. Then C) the outer skin was able to sit over the bones and dry out over time. (Becky Barnes)

The bones were scarred by tooth marks. And looking back at the skin, researchers saw signs of tooth and claw marks on them as well.

Whether it was ancient Cretaceous crocodiles or a juvenile T. rex, it was becoming clear that this dinosaur was not buried right after it died. Instead, scavengers had to have been able to feed on the carcass. This means that it probably had laid out exposed to the elements for weeks, months, or even longer.

So why didn't this soft tissue decompose then? After analysis, paleontologists think they know what happened.

During decomposition, the oxygen reacts with gases and fluids inside the body to speed up the process. But when scavengers fed on the body, many of these gases and fluids would've been released into the air. This meant that the skin that was left behind would've been able to dry out quite naturally, especially if it was exposed to lots of sunlight.

This is a bit like how leather (a material made from cured, or carefully dried, animal skin) is made. And wouldn't you know it, but it just so happens that drying out, or desiccation, is another common method of food preservation. (Think of desiccated coconut flakes, for example.)

Just one of many?

Now that researchers have identified this method as how Dakota was made, it has opened up a whole new way of thinking about dinosaur mummies.

Not only might there be more Dakotas out there waiting to be found, it might just be the most common way that a dino mummy would've been made. After all, carnivores scavenging a carcass happens a lot more often than flash floods do.

We can't wait to see what gets discovered next!

A section of Dakota's skin. (Creative Commons)

A section of Dakota's skin. (Creative Commons)