The pterosaur is one of those especially magical prehistoric creatures. Something like a bat crossed with a dragon, these flying reptiles conquered the skies ahead of birds, becoming the first animals with a backbone to fly. It achieved this by having an exceptionally light skeleton, made of thin, hollow bones.

But that same special trait has made them a rare find in the world of fossils. Those light, frail bones are next-to-impossible to preserve—more likely to be ground into dust than survive the journey to the present day. So any pterosaur find is a reason to be very excited! Even more so when it belongs to the largest pterosaur ever known from a certain time period.

Meet Dearc sgiathanach, or 'reptile from Skye', the largest Jurassic period pterosaur yet found!

Scotland's Jurassic playground

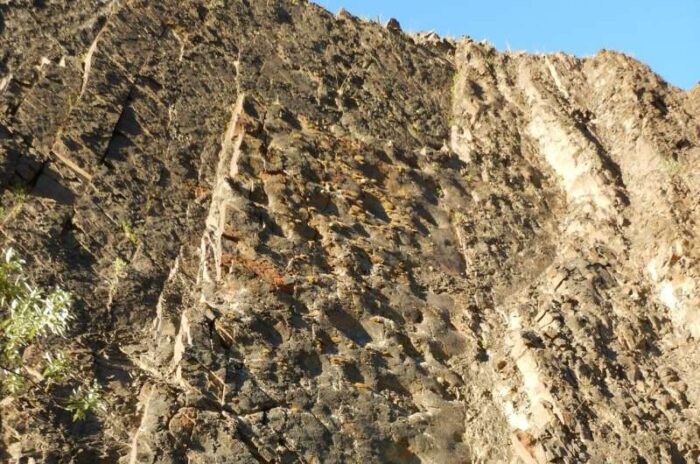

The exceptional fossil of the pterosaur. (Gregory F. Funston)

The Isle of Skye is a northwestern Scottish island that is the second largest in the country. It is well known for fishing, wildlife, and beautiful hilly scenery. But it is also famous for dinosaur fossils! You can find fossilized footprints on some of its rocky beaches and there are lots of prehistoric marine fossils found there, such as ichthyosaurs and ammonites.

This is because the rocks that are found exposed on the Isle of Skye date back between 200–145 million years—perfectly placed to the middle of the Jurassic period!

Enter D. sgiathanach. This new species was found in 2017 by graduate student Amelia Penny who was searching for dinosaur bones. But Amelia found something more amazing than she probably could have ever imagined. The best-preserved pterosaur bones ever found anywhere in Scotland.

An albatross-sized aerial predator

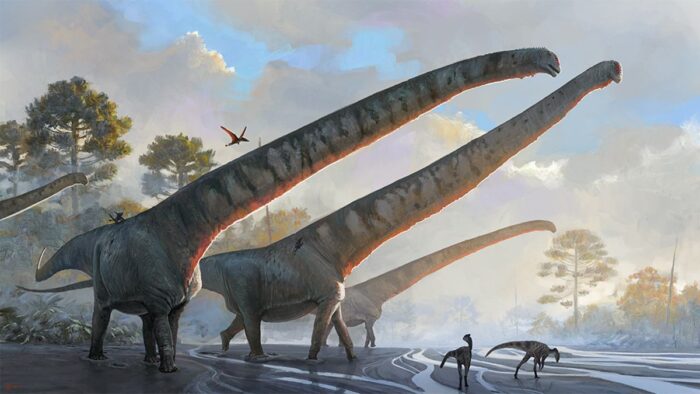

An artist's recreation of the D. sgiathanach. (Natalia Jagielska)

The estimated wingspan of this D. sgiathanach would've been about 2.5 m (8 ft.). Experts feel that, by looking at the development of the bones, that this fossil was of a juvenile/young adult. It is very possible that the full grown adult would've been as big as (or bigger than) the world's largest flying bird, the wandering albatross. That is a wingspan of 4 m (12 ft.)!

Along with the rest of the body, the fossil's skull was very intact. This allowed researchers to see dozens of sharp, needle-like, fish-snatching teeth. The animal also had large optic (eyes) sockets, which suggests excellent vision.

And while D. sgiathanach would've paled in size compared to a Cretaceous period giant like Quetzalcoatlus, this is a rare find of a very significant aerial predator. Will more skeletons of this animal be found in the future? That's the great thing about paleontology.

As much as we've found, we've still just scratched the surface of what is out there, buried in the rocks!

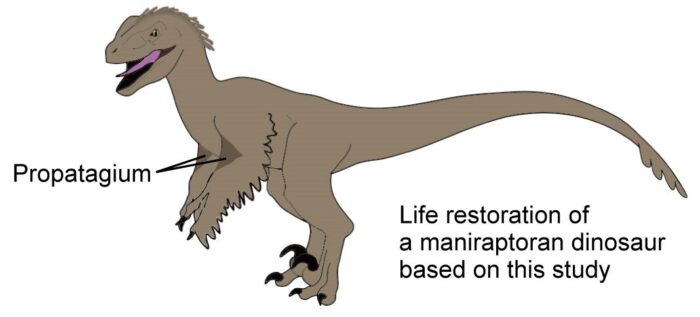

This art recreates how this pterosaur would've looked like next to an average Jurassic theropod dino. (Natalia Jagielska)

This art recreates how this pterosaur would've looked like next to an average Jurassic theropod dino. (Natalia Jagielska)

That is sort of terrifying