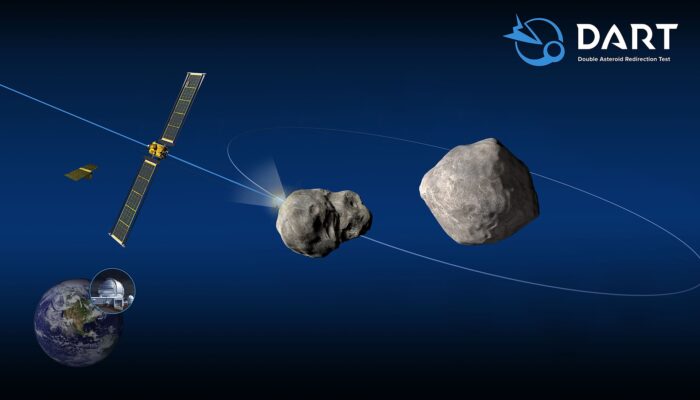

Last September, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) made contact.

This was a probe, about the size and shape of a small fridge. On September 26, it successfully struck the small asteroid Dimorphos, which itself is orbiting a larger asteroid, called Didymos.

The idea? Collide with the first asteroid hard enough to change its path around the second one. Just like the name says, a double asteroid redirection test!

This test wasn't being done because Dimorphos, or Didymos, were in danger of hitting Earth. It was see if a similar method could be used to change the path of an asteroid if one day there was one that might collide with our planet.

The results were impressive. By November, astronomers had seen enough to know that DART had changed Dimorphos' orbit around Didymos. The asteroid was now orbiting about 33 minutes faster than it did before the collision. Impressive!

But now new research is showing that there's something about the test that has taken researchers by surprise. DART alone could not have made Dimorphos' orbit change as much as it has.

So if it wasn't just DART ... then what was it? It's time to delve into the mysteries of space rocks!

Slow, steady stream of power

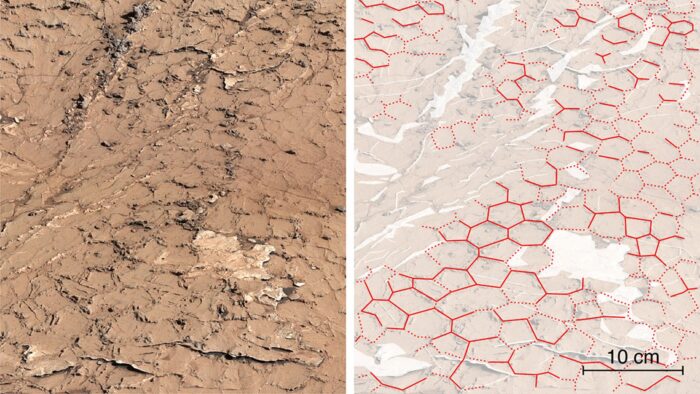

This image, taken by the SOAR telescope in Chile, shows the long plume of ejecta streaming off of Dimorphos after DART's impact. Research shows that this stream acted like an engine. (NASA/SOAR)

Astronomers using the NSF’s NOIRLab’s SOAR telescope in Chile captured the vast plume of dust and debris blasted from the surface of the asteroid Dimorphos by NASA’s DART spacecraft when it impacted on 26 September 2022. In this image, the more than 10,000 kilometer long dust trail — the ejecta that has been pushed away by the Sun’s radiation pressure, not unlike the tail of a comet — can be seen stretching from the center to the right-hand edge of the field of view.

According to calculations, the impact of DART should've only increased Dimorphos' orbit time by about seven minutes. Instead, it increased by over four times that amount. How did this happen? Did researchers misjudge the impact's force that badly?

No, according to papers by several astronomers. These experts focused on a few things. The size of the asteroid before and after impact. The amount of material (called ejecta) being released off of the asteroid after it was hit. And the length of time the ejecta was being released.

Together, they found that asteroid lost about 0.3 to 0.5 percent of its total mass. That may sound like a small number, but research also found that this material was still streaming off the asteroid for about two weeks after impact. This ejecta slowly transferred energy to the momentum of Dimorphos. You can think of it almost like a tiny booster rocket being attached to the asteroid for a couple weeks.

The result was that long after the impact, Dimorphos was still gaining speed—in the end, most of the change of speed was thanks not to DART's direct impact, but to the ejecta that the impact sent loose. Neat!

Timing is important

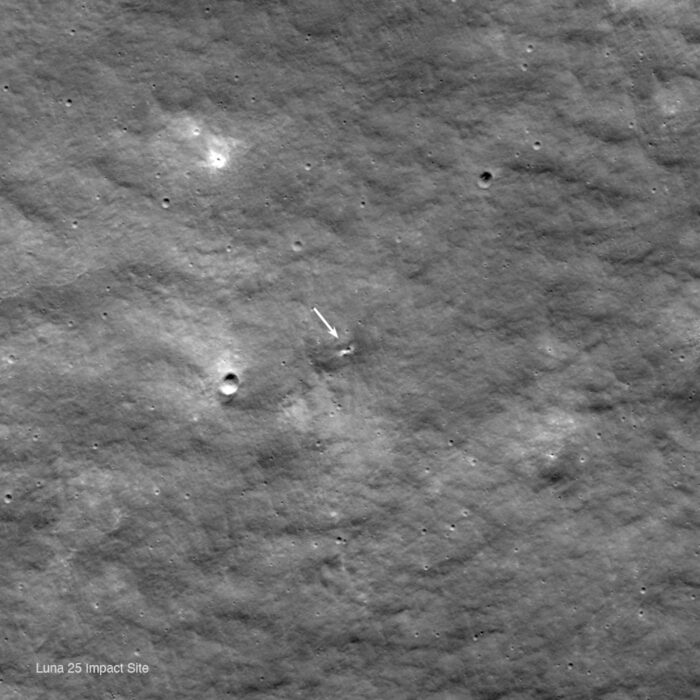

"Hi there!" This is the final full picture of the surface of Dimorphos, taken just before DART made impact. (NASA)

In the end, this means that missions like DART should be effective at redirecting an asteroid approaching Earth. If we know about the asteroid well enough in advance.

This will be the key to the success of a future mission like this one. Ideally, we know about the problem decades in advance. Fortunately, we have the detection technology to do just that! And it helps to know that no asteroid is on track to threaten Earth for well over 100 years. That's lots of time for this method to improve even more.

The DART mission has been a groundbreaking one for NASA. (NASA)

The DART mission has been a groundbreaking one for NASA. (NASA)

wow so cool um can I ask a question🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻

😮 😮 😮