Fungi are famous for their ability to thrive almost anywhere and break down almost anything.

They are master decomposers, the front line workers that turn a huge fallen tree into a nutrient-rich soil. Using acids, enzymes, and an army of root-like growths called mycelia, certain fungi are even able to feed on solid rocks and metals.

So it makes sense that researchers are constantly trying to see if any fungi can work their magic on one of the world's biggest pollutants.

New research out of the University of Sydney has shown that a pair of fungi are able to break down the common plastic polypropylene in just 140 days. The two fungi used in the experiment are Aspergillus terreus and Engyodontium album, which are commonly found in nature, including in our backyards.

Talk about the solution being right under our noses!

What is polypropylene?

This lid to a Tic Tacs box is made of polypropylene. (Wikimedia Commons)

Plastics are made from large, complex molecules called polymers. They are synthetic, or made by humans, and do not occur naturally. And most of them are made from chemicals found in fossil fuels like petroleum or natural gas (though there are 'bioplastics' that are made from things like corn.)

Some plastics are actually able to biodegrade, or break down on their own over time, in direct sunlight, for example.

But polypropylene (PP) is not one of those plastics.

PP is a very hardy, or strong, plastic. And a very common one. It is used to make everything from plastic bottles to laboratory containers to rope to furniture. And around one-third of plastic waste is PP, and that is a real problem.

How long does it last?

Unfortunately, polypropylene lasts forever, or close enough.

Scientists estimate that it will take hundreds of years for polypropylene to break down in nature. But they really don't know because PP was only first invented in 1951, so it hasn't even existed long enough for us to know for certain!

But whether polypropylene breaks down in 100 years, 450 years, or 1,000, it lasts too long to not be dangerous. Especially at the rate that plastic waste is growing worldwide.

Why not recycle?

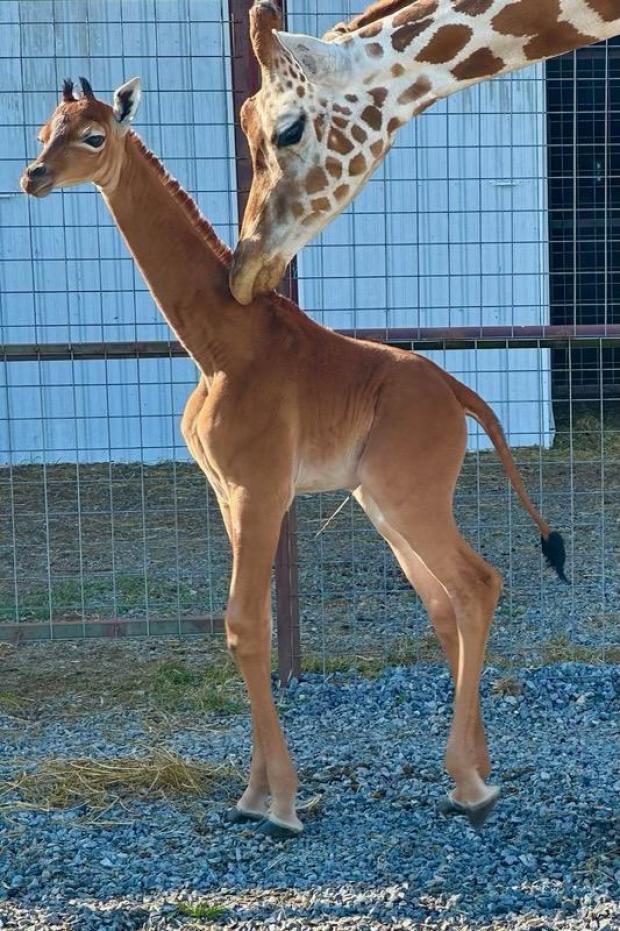

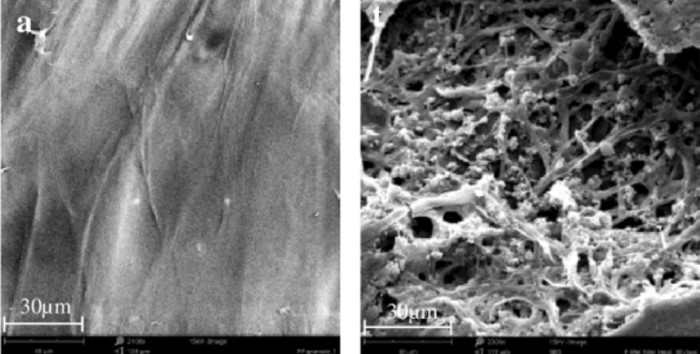

Munch, munch! These microscopic images show PP before (a) and during (b) the fungi feeding frenzy. (University of Sydney)

Recycling PP is possible, and we already do this in some cases.

But it needs to be kept separate from other plastics in order to be recycled properly. For this reason, most PP either gets incinerated (burned) or thrown in landfill (garbage dump).

This is what makes this new study so exciting. Instead of just throwing the plastic into the trash, people could simply unleash these fungi on it. Within a few months, that plastic could be turned into biologically safe waste. This is because the fungi breaks the plastic back down into basic elements that nature can handle.

Remarkable!

Not yet ready

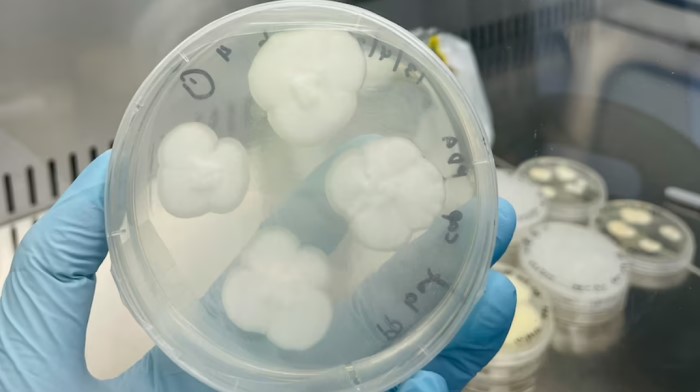

The fungi in a Petri dish. Proving this works in a lab is a big step, but more much work needs to be done for this to become a solution to our plastics problem. (University of Sydney)

Of course, there is a big difference between discovering this fungi in a lab and then turning it into a solution that countries can use.

That process, known as scaling up, requires a lot more research and testing. Scaling up is the difference between doing something in a tiny test tube and doing it on a massive industrial scale needed to address the thousands of millions of tonnes of polypropylene plastic waste out there.

In truth, these hungry fungi are not likely to be the only solution to our plastic problem. For example, they do need a helping hand to get going—in this experiment, the plastic was first exposed to powerful UV radiation, to help weaken the plastic and make it more munchable.

Instead, we will likely need many different approaches, all used together.

These approaches would include better compostable packaging, improved recycling technology, other types of plastic munchers (like certain bacteria and enzymes), and even packages that are made from fungi!

And then there is simply using less plastics overall!

These raw pellets of polypropylene plastic (PP) can be turned into almost anything. But they are also extremely difficult to get rid of once they are made. (ID 129828219 © Maciej Bledowski | Dreamstime.com)

These raw pellets of polypropylene plastic (PP) can be turned into almost anything. But they are also extremely difficult to get rid of once they are made. (ID 129828219 © Maciej Bledowski | Dreamstime.com)