On Friday, November 12, meteorologists warned residents in southern British Columbia that a severe rainstorm was on its way. It was expected to bring rain the entire weekend—in some areas, it could be enough to create flooding. As it turned out, what came was even worse than experts imagined.

That weekend broke rainfall records across the province. A month's worth of rain was dumped in just two days. Landslides shut down highways, stranding vehicles and people. Floods surrounded homes and flowed through neighbourhoods and towns. All in all, it has turned into one of the worst natural disasters in the history of the province.

Even worse, the weather really hasn't offered much of a break since then. Today's (Thursday, Nov 25) forecast in much of B.C. is for rain—and lots of it—seriously damaging the recovery and evacuation efforts. The Canadian government is holding emergency sessions to figure out how to bring more aid to areas as quickly as possible.

But it's one thing to help after a disaster has happened. It's another to understand why it happened in the first place, and to try and learn from that experience. In this case, experts say that the cause is actually nothing new, though our understanding of it is.

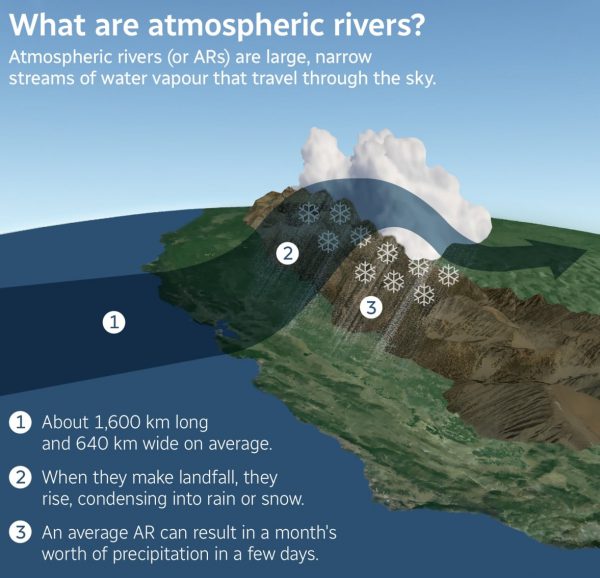

So let's take a moment to learn about atmospheric rivers.

A river in the sky

(NOAA/CBC News)

Atmospheric rivers (ARs) have been around forever, but the term is kind of new. It was first used in 1998 by Yong Zhu and Richard Newell, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). So what are they?

If you imagine a river flowing through the sky, you're not far off. They are enormous, long streams of water vapour. How big? They can stretch for over a thousand kilometres and be hundreds of kilometres wide. Contained within their clouds can be enough water to fill 25 Mississippi Rivers (one of the longest rivers in the United States). That is a lot of water!

They are formed in the tropical regions of the world, and then they flow through the atmosphere. Until they hit land. Then the water vapour condenses and a torrent of rain or snow is unleashed. This is especially true in a mountainous area, such as the B.C. coastline.

A scale of strength

Events like this are becoming more common. (Getty Embed)

Our understanding of ARs is still growing. It was only two years ago, in fact, that experts at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography decided to put together a scale for grading the strength of ARs. (This is something that we do with hurricanes to better understand how dangerous they might be.) The scale goes from AR1 to AR5, hitting from Weak to Moderate, Strong to Extreme, and finally, Exceptional.

This is helpful because not all ARs are bad news. An AR1 is entirely beneficial, for example, bringing needed precipitation to areas that may have be experiencing drought (no rain). Even AR2 and 3 can have really positive benefits.

But the higher the scale, the greater the danger to humans and our civilizations. The recent atmospheric rivers that have hit B.C.—there was actually a second one soon after the first—were both AR4 to AR5 and it showed. The effect was a once-in-a-century disaster that is still devastating the area.

Primed for a disaster

Though it looks peaceful from a distance, the effect of the storm has been devastating. (Getty Embed)

Of course, while ARs are entirely natural, there has been something extra happening in this case.

For example, a huge reason why the effect of this particular storm has been so bad has been because of landslides and mudslides. And these events were made more likely to happen because B.C.'s landscape has already been ravaged by drought and wildfires for years now.

Trees and other plants are a big part of what hold soil together, especially on mountains. Put together, their roots are like a giant net that connects the land. But if drought and fires remove those plants, then the land is more likely to get washed away after a large rainfall. Unfortunately this is exactly what happened.

The region was already in a fragile place.

What if it's not once in a lifetime?

Prime Minister Trudeau is facing a lot of pressure to improve his response to climate change. (Getty Embed)

Natural disasters are not new. Rains, floods, wildfires, drought ... these are all natural processes that, overall, add to the cycle of life on the planet. They remove old, decaying growth, clear the land, and set things up for new life.

But, as with wildfires and hurricanes, the strength and frequency of these big events is new. And it is happening because of climate change.

Yesterday in Parliament, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said the effects of climate change are arriving "sooner than expected, and they are devastating." This matches the messages from many scientists. They say that due to climate change, atmospheric rivers will go from lasting one or two days to nearly a week.

This is why the recent debate in Parliament over addressing this issue got particularly heated. MPs from the NDP and Green Party have been pushing Trudeau and the Liberals to act. They want Canada to make a move to green energy sooner. Meanwhile, the Conservatives have talked about the jobs that are at risk by moving away from fossil fuels too fast (many Canadians work in these industries).

No matter where you stand on this issue, it is quickly becoming one that people cannot ignore.

An atmospheric river creates an enormous amount of rainfall in a very short time period. (Photo 60281732 © Mrtwister | Dreamstime.com)

An atmospheric river creates an enormous amount of rainfall in a very short time period. (Photo 60281732 © Mrtwister | Dreamstime.com)

I hope my cousins are safe there 😥 🙁