A supernova — the death explosion of a large star — is never a small thing.

We're talking about the moment when an enormous ball of gas much bigger than our own Sun suddenly goes ka-blooey in a devastating flash of energy seen across the universe. It's a huge deal.

So when astronomers say that they've just seen the brightest supernova ever recorded? Well, you just know that is something beyond.

Named SN2016aps, this was a ginormous explosion that occurred 3.6 billion light years from Earth. What's more, it was a truly unusual supernova whose mysteries scientists are still trying to unravel.

What happened?

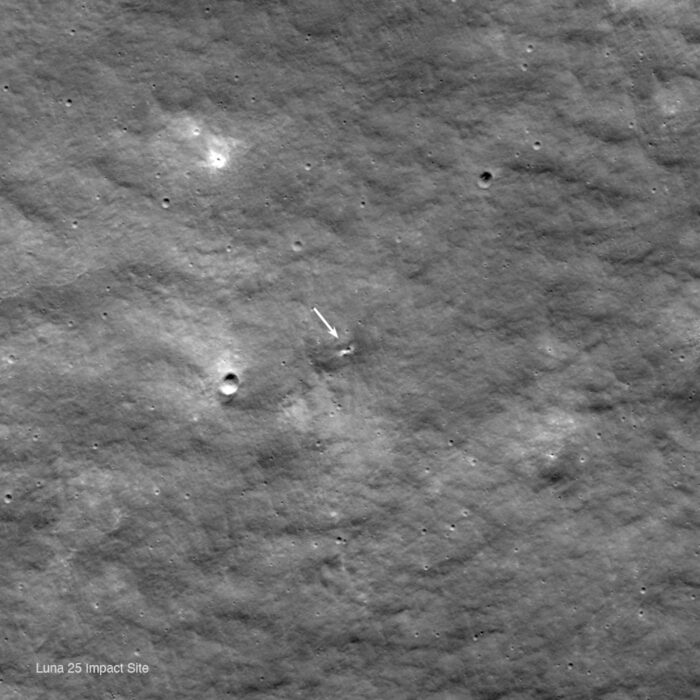

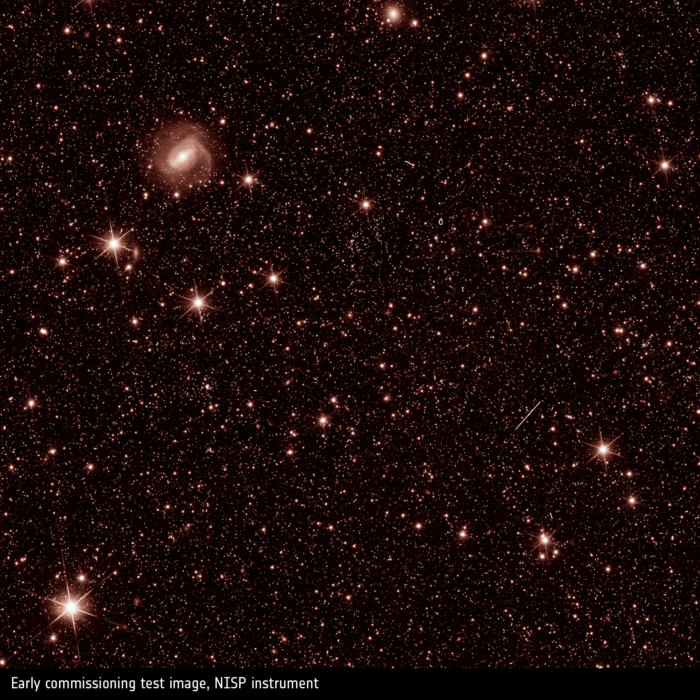

This supernova was observed by the Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii. (Getty Embed)

SN2016aps (named because it was discovered in 2016) released five times the observable light, or radiation, of a typical supernova. And the question is: How?

The first response is that it was just a really, really huge star that exploded. Estimates are that this supernova came from something up to 100 times the mass of the Sun.

So SN2016aps was a supergiant star that went supernova. Case closed, right? You'd think so, but...

Too much hydrogen

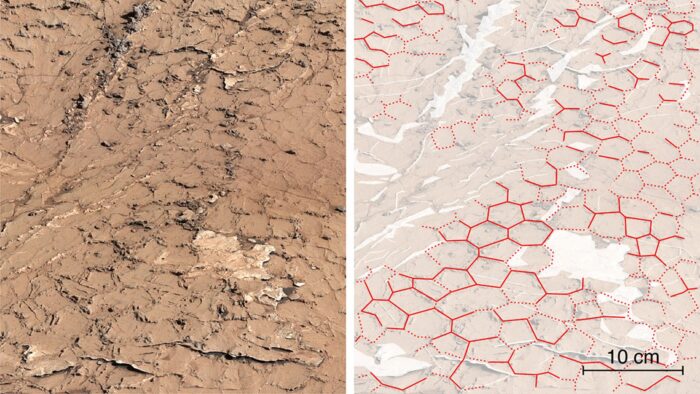

Understanding how supergiant stars explode — and what they leave behind — is something scientists still have a lot to learn about. (NASA, ESA, and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA))

When scientists looked at the leftovers of this explosion, they noticed something curious. There was a lot of hydrogen.

This is unusual because before extremely large stars go supernova, they have burned off most of their hydrogen. In other words, though the amount of light is right, a supergiant's supernova shouldn't look like this.

But what about two smaller (though still large) stars coming together and exploding? Wait, that can happen?

Say it together: Pulsational pair-instability

Scientists believe that it can and they call it pulsational pair-instability. It's when two stars come together while one is near death, leading to an explosion of their combined stellar mass. Each star is still large — about 50 to 60 times the mass of our Sun — but they haven't burned off all of that hydrogen yet.

This phenomenon has never been observed before — it was only a hypothesis. Now they're wondering if this brightest supernova is the proof they've been searching for.

The numbers seem to add up, but that's not how science works. It's going to take more analysis to know just what caused SN2016aps. But until then, we can marvel at the fact that in a star(s) that probably lived about 10 million years, we just happened to be around for its grand finale.

That was one bright light!

Better break out your sunglasses, it's SN2016aps! (© Spacedrone808 - Dreamstime.com)

Better break out your sunglasses, it's SN2016aps! (© Spacedrone808 - Dreamstime.com)

BOOM!

I don’t think

I’m completely free minded