Montreal is a magnificent city known for many things. Beautiful buildings. French language and culture. Art. Food. Hockey.

But one thing that you might not know about Canada's second largest city is that it is home to one of the most successful international environmental agreements ever signed.

The Montreal Protocol.

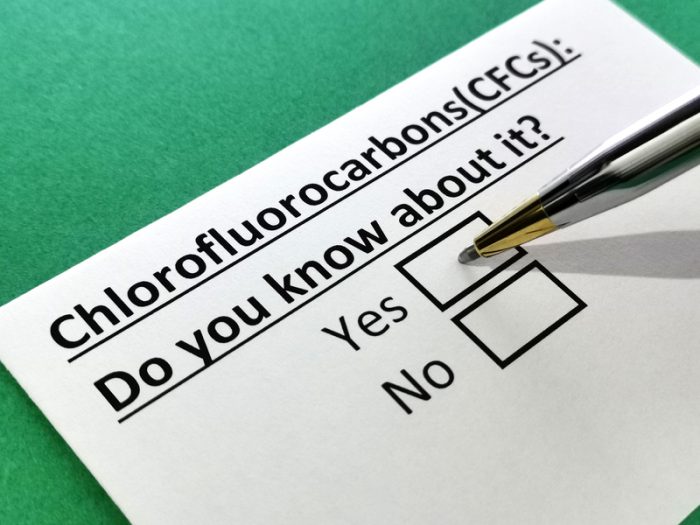

A new study recently explained how this 1987 ban on chemicals known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) bought us all sorts of benefits, even more than we knew before. And at a time when the world is facing some big decisions on climate, it is an awesome example of the power that humanity has when we all work together.

What are CFCs and why did we use them?

CFCs are a type of compound known as hydrocarbons. In the 20th century, scientists found that CFCs could do all sorts of useful things. In particular, they were useful as refrigerants (the fluid used in fridges and other cooling devices), fire extinguishers, and propellants in aerosol cans (in other words, the stuff that let bug spray zoom out of a can). These things were very useful, and so CFCs were found in hundreds of household and industrial items.

Why are CFCs dangerous?

This crisis led many people to learn about what ozone was and why it was important. (Getty Embed)

Unfortunately, using lots of CFCs created a big problem. When these compounds were released into the atmosphere, they reacted with an important molecule in the atmosphere—ozone, or O3. This reaction turned ozone into oxygen molecules, or O2. That might not sound that bad at first. After all, oxygen is what we use to breathe. Pretty important stuff!

But ozone is extremely important as well, especially in our atmosphere. Ozone is very good at absorbing ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, or UVs. The ozone layer is a layer in the stratosphere that covers almost the entire Earth, protecting us from these UVs. Without this shield, all life on Earth would be exposed to deadly amounts of radiation.

The 'hole'

An image from 1992 showing the condition of the ozone 'hole'. It has since been made much smaller thanks to the protocol. (Getty Embed)

This issue became a reality when atmospheric scientists found something in the 1970s and 80s. A large area of the ozone layer in Antarctica was being depleted, or made less strong. And the size of this area of depletion was growing every year. This area became known as a 'hole' in the ozone layer.

To be clear, it wasn't technically an actual hole in the ozone. Like a lot of things in science, the truth is way more complex than that (which is why it takes a while to become a really good atmospheric scientist!). But calling it a 'hole' made the message—and danger—more clear.

A very important 'shield' was getting weaker, and that affected the entire planet.

Making the ban

According to the ban, leftover CFCs found in old fridges must be disposed of properly. (Getty Embed)

Fortunately, scientists were able to understand why this 'hole' was forming. The record amount of CFCs that were being sprayed out on Earth's surface were circulating up into the high atmosphere. And they were breaking down the ozone. Even though the science was complex, the solution was simple.

Stop using the CFCs and the ozone can have a chance to heal itself.

Though there was strong resistance at first from companies that used CFCs in their products, that ban was exactly what happened. On September 16, 1987, members from 46 nations from around the world met in Montreal and signed an agreement to ban CFCs. The Montreal Protocol was later ratified, or agreed to, by 198 countries.

It came into full effect on January 1, 1989, giving all countries a chance to prepare for and adjust to the ban. It remains in effect today.

Why is the Montreal Protocol so great?

Today, the Montreal Protocol remains the only UN treaty that has been agreed to by every single nation on Earth. That's remarkable. And hopeful, too.

Here are three reasons why the Montreal Protocol is such an inspiring example for us to follow today.

- Quickly done: For an international agreement, it happened incredibly fast. From the time the problem was first discovered by scientists in 1973, it took only fourteen years for the protocol to be agreed to. That might seem like a long time, but it is quick for this sort of thing—and it proves that complicated challenges can be faced properly by large groups.

- It worked: Since it was signed, the agreement has delivered on its promise. Around the world, the ozone has either stabilized (stayed the same) or strengthened. Nowhere has the 'hole' continued to grow. It's important to be able to see how the world's action on the environment can lead to positive results—and how these results help everyone, not just certain parts of the world.

- Bonus stuff: The Montreal Protocol would be a success if it just did what we thought it was supposed to do. But a new international study suggests that it's going to do even more than that—in the future! Their data shows that without the Montreal Protocol, the ozone layer would be collapsing by the 2040s, which would damage plant life around the world. Plant life that normally would be eating up carbon. In short, without the Montreal Protocol, we would be eventually be losing yet another extremely important barrier against climate change.

Whew. Okay, that was a lot to digest! Thanks for sticking with us! For more thoughts on climate change, check out this post from last week, which talks about it in more detail and is full of links across our site.

CFCs are an environmental problem that humanity successfully addressed with the Montreal Protocol. (ID 186631128 © Yee Xin Tan | Dreamstime.com)

CFCs are an environmental problem that humanity successfully addressed with the Montreal Protocol. (ID 186631128 © Yee Xin Tan | Dreamstime.com)