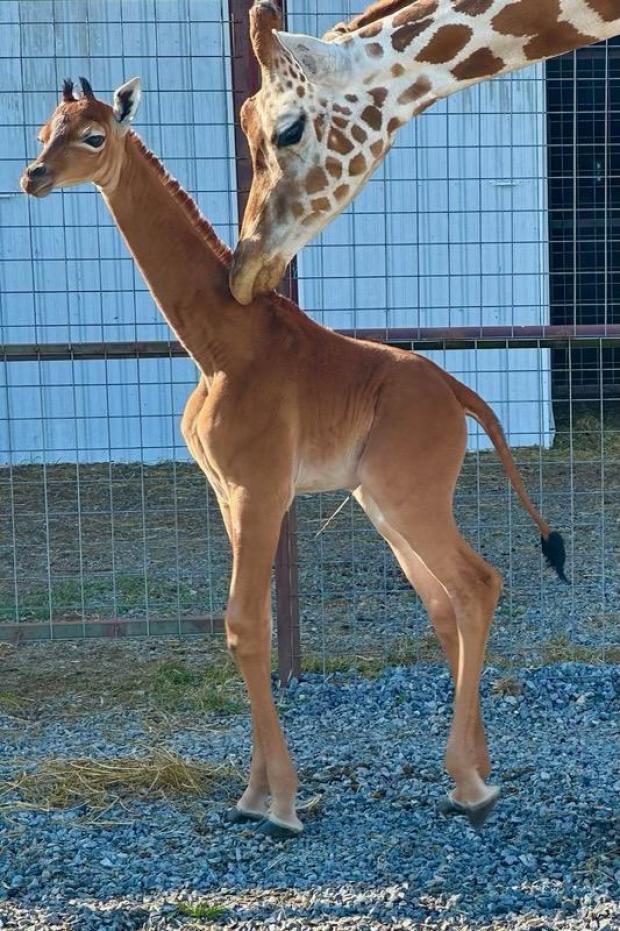

No, this is not an image of invading jellyfish aliens from Mars. It is a red sprite.

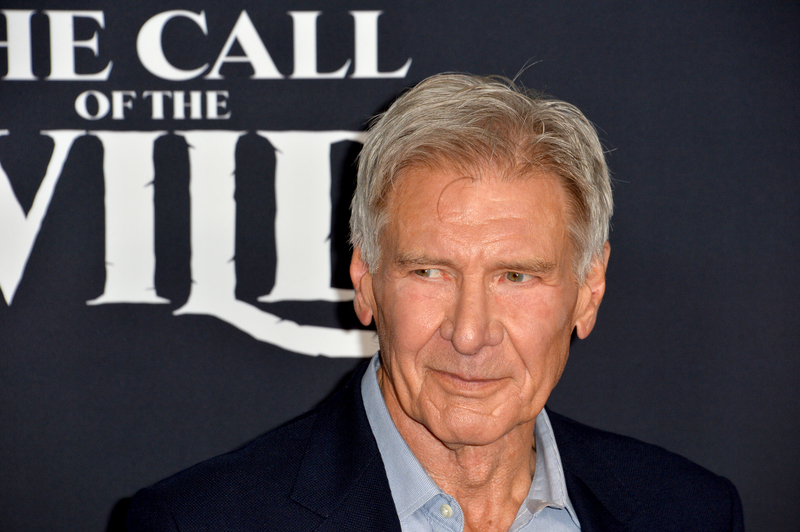

This image was taken by an American photographer Stephen Hummel. He works at the McDonald Observatory in Fort Davis, Texas as a dark sky specialist. This is someone who is an expert at picking out stars and constellations in conditions that are far away from the light interference given off by cities.

In this case, the sprite is known as a jellyfish sprite because it looks like, well, a big jellyfish! It's a strange and beautiful photograph, for sure.

What exactly are sprites? And why don't they look at all familiar?

High and mighty

Photographer Stephen Hummel's time skywatching at Texas' McDonald Observatory clearly paid off. (Getty Embed)

Usually, lightning occurs relatively low in the atmosphere, often striking targets on the ground. But sprites are a type of electrical discharge that occur far up in the Earth's atmosphere—about 60 to 80 kilometres (37 to 50 miles) up! They exist as a kind of balance to what we think of as normal lightning.

When lightning strikes, it releases an immense amount of positively charged energy. But the way nature works is that it doesn't like to have too much of one type of charge in an area—it will try to release an equal, opposite charge somewhere else to keep stuff balanced. Can you guess how it does this?

Yep, sprites!

Why don't we know about it?

![]()

A sprite as seen from the ISS. It is the dull red smudge above the bright lightning cloud in the upper right. (NASA)

If you've never heard of sprites before, there are really good reasons. And you're not alone. Sprites have only been known to science since 1989! Here's why.

Not only are they super high up, they are almost always obscured by clouds. Makes sense—you need a strong lightning storm below to create them, and it's not easy to look through a big storm cloud! They are also appear and disappear very quickly. A red sprite lasts only about a tenth of a second.

All of these traits mean that red sprites are more likely to be seen by astronauts on the International Space Station than humans on the ground. And if someone on Earth does see one—as Stephen Hummel did—chances are that they are persistent. Want proof?

To capture that amazing image at the top of this post, Stephen shot 4.5 hours of film. 270 minutes of images, just to get that millisecond glimpse of time. That's dedication. And well worth it, too!

Blink and you'll miss it! Some truly epic jellyfish red sprite. (Stephen Hummel)

Blink and you'll miss it! Some truly epic jellyfish red sprite. (Stephen Hummel)

This is very cool! Does anyone else find the video’s music bordering creepy?

Who knew?? 😀