Do you like cooking and baking shows?

Ones where chefs are surprised by mystery ingredients and given a half hour to create a new dish? Or where bakers try to fool people with cakes that look like real everyday objects?

Whether that's your thing or you're the kind of person who would rather just tuck into a simple burger and call it a day, you have to admit: Humans know how to do some neat stuff with their food!

But where did it all begin? When did humans start learning to cook, not just eat?

Most of us would have no problem guessing that our culinary history goes back several thousands of years. But a recent study from the University of Liverpool says that examples of humans seasoning and being creative with their food go back 70,000 years and longer!

And it was not just Homo sapiens (a.k.a. modern humans) that knew these tricks. Neanderthals were in on the fun, too!

Bitter and sharp

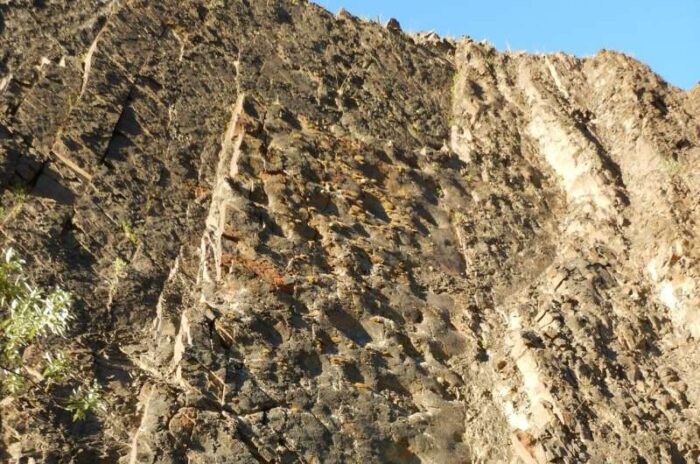

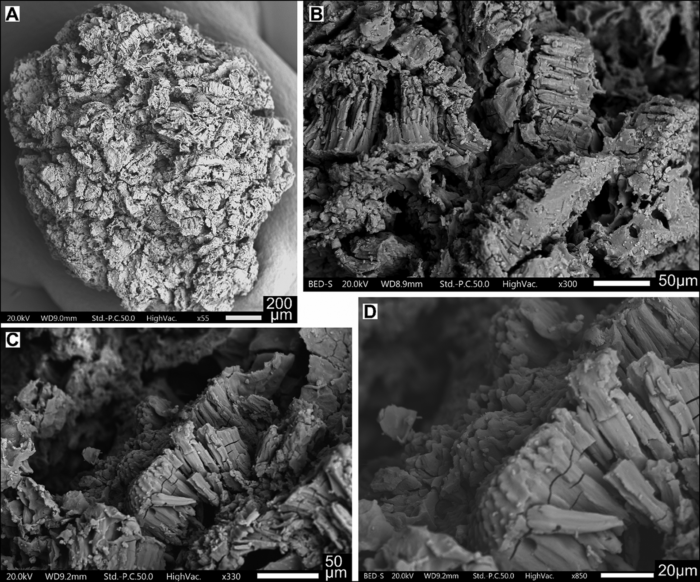

Electron microscope images of the food found in Shanidar Cave, in Iraqi Kurdistan. (SEM micrographs taken by C. Kabukcu)

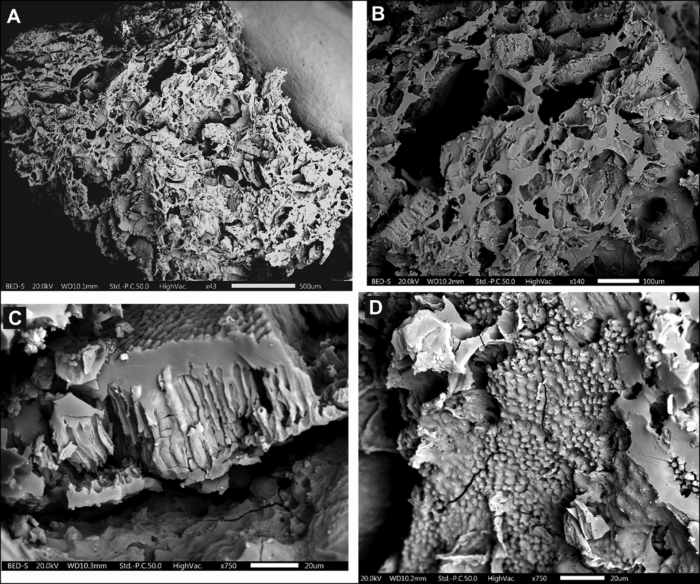

The study looked at charred remains of food that was found in certain caves where bones of ancient humans have been found. These 'leftovers' kind of look like really, really dried out, burnt breads. They were likely mixtures that were made into either a type of bread or a porridge.

The locations included food from:

- Franchthi Cave in Greece, where early humans lived from 11,500 to 13,000 years ago

- Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan, where humans lived around 40,000 years ago, and Neanderthals lived around 70,000 years ago

After looking through an electron microscope, the researchers found many examples of pulses (seeds) in the food from both locations. These included pulses of wild mustard, terebinth (wild pistachio), grass pea, wild pea, and more. These seasonings had been soaked, ground, and mashed into these bread/porridge mixtures.

The pulses were not essential to the structural content of the food. (In other words, they didn't help make the bread or batter come together.) They appear to have been there for one reason only.

For their flavour. (Which in these cases, are mostly a bitter and sharp flavour, if you're curious!)

Similar approach across thousands of miles

This map shows the distance between the two caves that were studied. (C. Kabukcu, et al)

One of the most striking things about this study is not just how old these 'leftovers' are. It is how far apart they are.

Greece and Iraq are separated by thousands of kilometres. Especially in the ancient world, such a distance is significant. It helps to show that this was not just some regional phenomenon that happened by accident. This was something that our distant relatives were doing regularly as a part of their daily meals.

It suggests that in addition to the tubers (such as potatoes or carrots) and meat and fish that ancient humans ate, they knew how to be creative and expressive with their meals. It was not just about filling their tummies.

We knew our love of making delicious meals had to come from somewhere! Now who's ready for the next season of The Great Paleolithic Baking Show?

It might not look like much, but these charred remains of food from Franchthi Cave in Greece are full of examples of curious cooking! (SEM micrographs taken by C. Kabukcu)

It might not look like much, but these charred remains of food from Franchthi Cave in Greece are full of examples of curious cooking! (SEM micrographs taken by C. Kabukcu)