Fossils are like a jigsaw puzzle. Without all the pieces. And without that handy picture on the box that tells you what it's all supposed to look like in the end.

Instead, paleontologists—the experts who spend their lives trying to solve these prehistoric puzzles—must use clues from the past, from other similar fossils, and even from current living things to put it all together. And even the best in the business don't always get it right the first time.

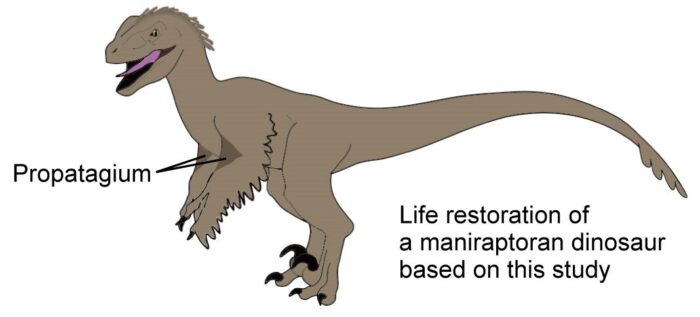

That's why our understanding of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals is always changing. As more fossils are found—and as the technology used to analyze those fossils improves—the experts have the chance to update their understandings. Probably the most famous example of this is that we now know that many dinosaurs had feathers. But there are other examples, too.

Take this brand new finding about Tanystropheus. This prehistoric reptile wasn't a dinosaur—its hip bones were more lizard-like, making it closer to an iguana or crocodile. But exactly what it looked like—and how it lived—has been a mystery for 170 years.

A long-necked mystery that, thanks to modern technology, paleontologists believe they've finally solved!

What are these bones?

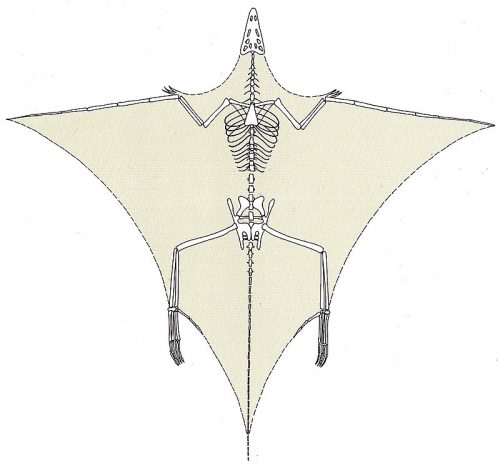

The reason for the confusion? When the first Tanystropheus fossil was discovered in 1852, it had these long bones that left researchers baffled. In fact, they thought it was some kind of pterosaur, or flying reptile. This was what the first restoration of the creature looked like.

The first restoration of Tanystropheus, then called Tribelesodon. (Wikimedia Commons)

Whoops! But such a mistake is also very understandable. In the mid-1800s, paleontology was exceptionally difficult work. There were no computer scans, and often the fossils that were found were the first of their kind. With little to compare the bones to and no way to scan inside the fossil, they did the best they could.

Eventually, the understanding of Tanystropheus went from it being a pterosaur with wide wings to it being a distant crocodile relative with a very long neck. (So that's what those bones were for!) But many questions remained as to how it lived. Did it live on land at all? Or did it mostly swim? What did it eat? Insects? Fish?

These questions are even harder to answer when experts were dealing with skulls that look like this:

The rather smooshed skull of a Tanystropheus. (Wikimedia Commons)

How do you make sense of such a crushed skull? You scan it!

Scan reveals new answers

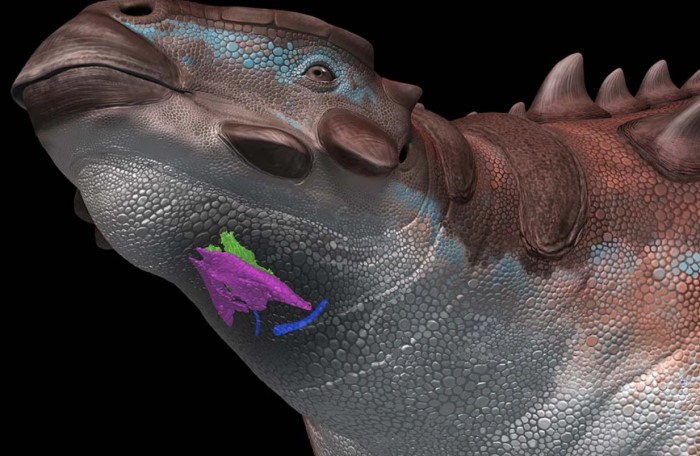

The 3D restoration of the animal's head helped scientists understand the animal. (Spiekman et al., Current Biology, 2020)

Thanks to a series of CT scans done last August on a Tanystropheus skull, researchers have been able to put together a 3D restoration of the animal's bones that someone in 1852 could only dream of seeing.

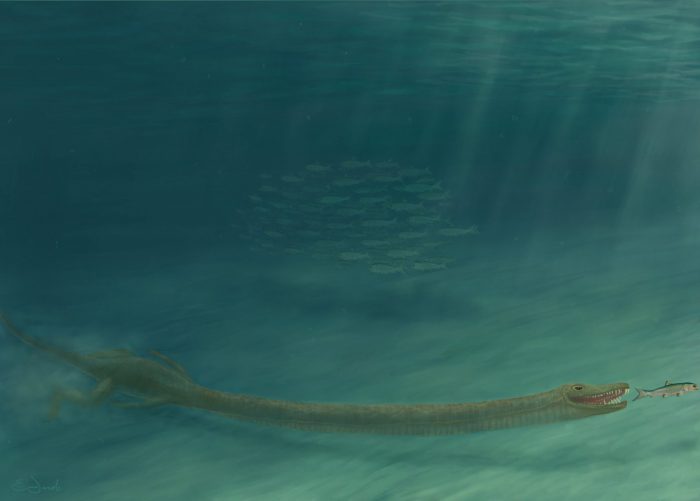

The end result is an animal that had a flatten head and nostrils on the top of its head. These are telltale signs of an air-breathing animal that spent most of its time in water. Its head would've floated still near the surface, waiting for prey to swim past. Its front teeth were also curved and overlapping—perfectly made to grasp wriggling fish and other squid-like animals.

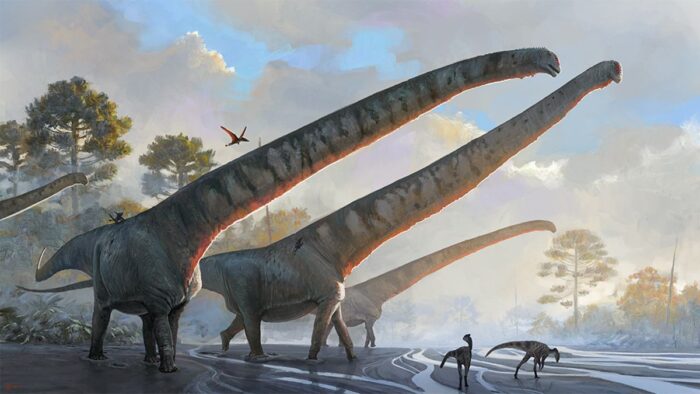

Add these details to its super long neck and crocodile body, and you have a truly unique animal. A sleek 6-metre (20 foot) long predator that would've skillfully hunted swimming prey 240 million years ago. What a cool animal!

And here it is! A new illustration of Tanystropheus. (Emma Finley-Jacob)

Solving some puzzles can really be worth the wait!

Tanystropheus was a fish-eating marine reptile that lived about 240 million years ago in the Triassic Period. Figuring this out hasn't been easy! (Wikimedia Commons)

Tanystropheus was a fish-eating marine reptile that lived about 240 million years ago in the Triassic Period. Figuring this out hasn't been easy! (Wikimedia Commons)