May 7 to 22 is Science Odyssey, a celebration of all things science! OWLconnected is recognizing this two-week event with lots of science content, as well as with an amazing contest, presented by our friends at the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Details are at the end of this post—be sure to enter!

From student to leader

At just 25 years old, Alex Deans has traveled the world, met royalty, delivered speeches in arenas, been named one of the most promising young Canadians of his generation, and even had a minor planet named after him(!).

And, in a way, it all started with science.

Before he was even a teenager, Alex was using his curiosity, compassion, and smarts to enter science fairs. His first big invention—a navigation device for the blind called iAid—gained international acclaim. From there, he's worked with GM/Chevrolet, appeared at WE Day and done TED Talks, and is currently working on a new medical treatment app called Pickle. Amazing!

Alex's life of invention

(Courtesy of Alex Deans)

We caught up with Alex to ask about how science opened doors for him, what it's like having a space rock named after you, and what he's working on now.

OWLconnected: Let's go back to when you were in grade school. What did you think of science then?

Alex Deans: I don't think I thought of science as something that was organized or that I had to study. It was something that I stumbled upon very naturally because I was curious. I liked to fiddle with things and I spent a lot of my time outdoors just trying to build stuff. Creating and observing the world around me. By doing so you figure out how things work and why things work the way they do. So I very naturally fell into that.

But I don't remember science class being my favorite class in Grade 2 or 3. It was gym! Then as I got through higher grades—Grade 8, 9, 10—I started channeling some of that curiosity into science fair projects; fiddling with robotic technology and directing those talents a bit more.

Being outside a lot helped give Alex a sense of curiosity. (Courtesy of Alex Deans)

OC: You mention how you were outside a lot observing nature. Was that your earliest approach to science, and then the tech side came later?

AD: Yeah, I think it really began with observation. And then asking questions. I had a really great resource—my parents! They were not in science necessarily, but were always willing to investigate questions that I asked and help me answer them.

So I wanted to know, Why does a tree grow upright instead of sideways? Why are certain leaves bigger than others? Very simple questions, but when you start to ask them, you kind of realize how things work. My parents were really instrumental in answering my early questions and getting me interested in that way of thinking.

OC: Eventually, you started building tech. Was it intimidating at first?

AD: I think my abilities grew with curiosity. A lot of people think that I had that plan for the technology at the beginning, but really I had no idea what I was doing! I was just fiddling around for fun and it turned into something. There was really no pressure on me, it was just something that I was learning for enjoyment. Then the interest in technology itself—and the skills in technology—came along later.

A prototype of Alex's first big invention, the iAid. (Courtesy of Alex Deans)

OC: Speaking of tech, we first heard your name in connection with iAid, which has been exhibited at the Ontario Science Centre...

AD: It's been on exhibit there for a few years, and it's just starting at the Bombardier museum in Quebec.

OC: Great! Will that become an available product one day?

AD: I took it up to the point of making it functionally work. Then I realized it's a much longer game in terms of getting it to market [ready to be sold]. There's more of the health regulation stuff that comes with it being used outdoors—I wasn't really interested in pursuing that, so I left the project with the CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind). Then I started on some of new projects in healthcare.

OC: One of the things that you discovered is that executing an idea—even one that's quite simple—at some point involves a lot of different people. With iAid, was there a moment where you felt frustration or disappointment?

AD: It was a combination of both throughout the whole experience. It was equally frustrating and equally exciting throughout all the years that I spent doing it. Because that's the thing about development. Everything seems simple when you write down a paper and then when you try to do it, everything turns into a problem. So each of those problems is frustrating, but it's also so exciting and so rewarding when you overcome it!

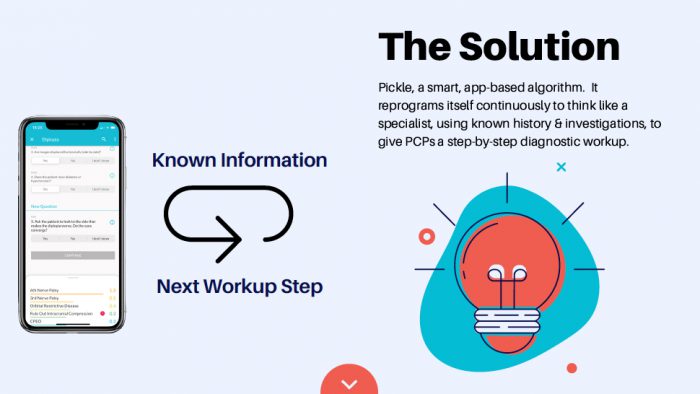

A screenshot from a presentation on Pickle, his newest app project. (Courtesy of Alex Deans)

OC: Okay, speaking excitement, what are you working on right now? Anything you can talk about?

AD: I'm working on a new app called Pickle! I started medical school and one of the problems I saw was that a lot of patients were coming in (to clinics) with symptoms that didn't have a clear diagnosis [their exact illness wasn't obvious]. This led to having unnecessary tests and confusion.

So the idea was how can we help doctors get to a diagnosis more efficiently? That's how Pickle was born. It essentially uses AI algorithms (like problem solving programs) that we designed that take the known history about the patient and then infer with the next best step is to get to a diagnosis. It tries to mimic the way a medical specialist thinks.

OC: That sounds very useful!

AD: We started by building (the app's) algorithms for eye problems, because that's my that's where I've been rooted for the last few years. We built it out for patients with loss of vision and red eye complaints. We tested it in Windsor with 200 patients, and we saw increases in diagnostic accuracy from 54 percent to upwards of 93 percent with Pickle. So that was really encouraging!

Now we're doing algorithms in other fields and have physicians at universities like Duke, Toronto, and Harvard working across development. So that's been my main focus over these last two years.

OC: That's fantastic! So, in other news... you have a minor planet named after you! Do you ever look around and think, How is this happening?

AD: Yeah, it's very strange, but is one of the things that I look back at and still think, Okay. That's pretty cool!

OC: Can you point it out? Do you know where it is in space?

AD: Yeah. The people at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) gave me a printout of its orbit. I know it's far away from Earth, so it's not gonna be responsible for colliding into our planet anytime soon. That was my one requirement (for it being named after me).

OC: Yes, please! No near-Earth collisions! Could you talk about science fairs and what they have meant to you? You participated in a few of them.

AD: Oh, loads of them!

Alex at the Canada Wide Science Fair. (Courtesy of Alex Deans)

OC: How do you feel they helped you?

AD: From Grade 3 onward, science fairs were the best part of school for me. They were kind of like a ritual in my house from November to February. In the of dead winter, that was prime science fair development phase.

Grade 3 was my intro to science fairs. My sister and I tag-teamed on a project—we wanted to make paper out of leaves. So we collected all the leaves from outside, ground them all up, and put them in between two sheets of door screens.

And then we were supposed to both put some weight and pressure on the leaves to sandwich them into paper, but my sister split. So I remember sitting there for five hours on top of these two screens trying to push it down on my body weight!

And that was my first science fair project—that little four by four centimetre sheet of paper that we could write on. I felt pretty accomplished at the end of making it.

Young Alex working on yet another science fair project. (Courtesy of Alex Deans)

OC: Success!

AD: But science fairs themselves taught me a lot. How do you state the problem clearly? How do you design a solution that has strong parameters? How do you set expectations and goals for yourself? And this has followed me into leadership roles. I know how to set goals for the team or what we have to work towards.

Science fairs taught me how to sell an idea. It taught me how to talk to people and how to articulate my ideas. That was probably the best lesson I got out of school.

OC: That last point is really interesting. There's always the stereotype of the shy, awkward scientist. But your time as an inventor is full of communication and reaching out to people.

AD: Science is highly collaborative. One person never has all the answers. You meet a lot of different people throughout different projects. I made a lot of friends through science.

Contest alert

Don't forget to enter the Science Odyssey Contest! CLICK HERE TO ENTER.

Alex has grown from a student science fair prodigy to in demand public speaker and inventor. (Courtesy of Alex Deans)

Alex has grown from a student science fair prodigy to in demand public speaker and inventor. (Courtesy of Alex Deans)