A recent discovery of a 16 million-year-old tardigrade fossil is giving researchers a rare glimpse into the past of these animals.

Encased in amber—hardened tree sap—this is only the third fossil of its kind ever found. Because as almost indestructible and common as tardigrades are, next to nothing is known about their evolution.

How can that be? Why are they so difficult to preserve as fossils?

Everything disappears

Tardigrades, a.k.a. water bears, can be found in almost every environment on Earth. They can survive pretty much everything you throw at them. Drought, boiling, ice, crushing pressure, the vacuum of space. They can even completely dry themselves out and be brought back to life many years later—like with some prepackaged dehydrated space food, except it's a living thing!

But finding a preserved tardigrade is rare. This comes down to the fact that when one of these creatures do die, the materials they are made of don't survive fossilization. Without any bones or shell, they simply break down completely and are reabsorbed into the cycle of life.

Amber to the rescue

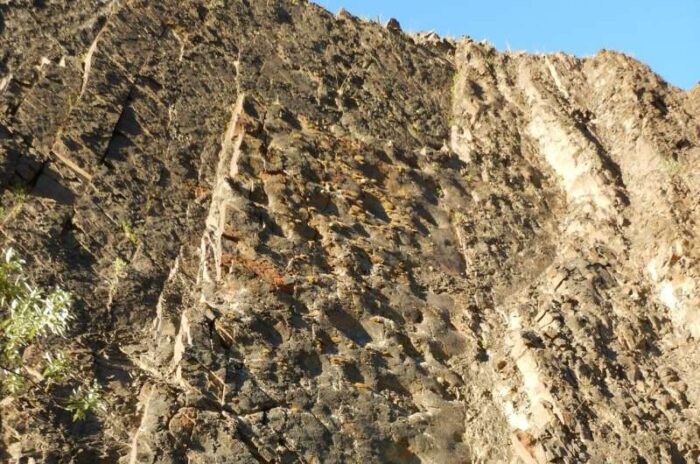

Even the most delicate creatures can be preserved in amber. (Getty Embed)

One of the only exceptions to this is amber. Amber is already known for its ability to preserve fragile organic components like feathers, hair, fur, wings, skin, scales, and more. Whereas this stuff normally just decomposes, amber freezes it in time. Or more accurately, freezes it within a golden, jewel-like capsule.

In other words, it is the perfect method to preserve a tardigrade. When sealed in amber, it essentially looks like it died yesterday—even if it's 16 million years old. Speaking of which .... let's talk about that tardigrade fossil!

A new species?

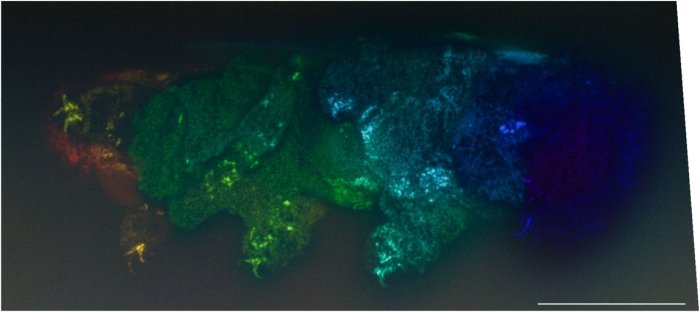

Under fluorescent imaging, the fossil shimmers like a jewel! (Mapalo et al., Proc. R. Soc. B, 2021)

The chunk of amber the fossil was found in was already full of several insects and bug fossils. In fact, the tardigrade was easy to miss—to the naked eye it was smaller than an air bubble and looked like a tiny scratch. It wasn't until the amber was investigated under special microscopes that they knew what it really was.

Once they knew they had a tardigrade on their hands, scientists were able to take images of the animal, even scanning its insides to understand how its guts were structured. This allowed them to determine that this specimen is of a species that is slightly different to modern tardigrades. This makes sense—it is 16 million years old, after all!

Alongside the two other tardigrade fossils—which are 90 million and 72 million years old—scientists are able to begin to piece together a vague picture of how these animals changed over the eons. The discovery also highlights the fact that we may already have dozens, hundreds, even thousands of tardigrade fossils in our possession. They're so small, they're easy for even experts to miss.

Time to double check that amber, people!

Next to a dime for scale, this tardigrade fossil is invisible to the naked eye. (Phillip Barden/Harvard/NJIT)

Next to a dime for scale, this tardigrade fossil is invisible to the naked eye. (Phillip Barden/Harvard/NJIT)