What is an art gallery?

Well, that's easy, right? It's a place that displays pieces of art—like paintings and sculptures—so that the public can see and enjoy them. Simple as that. But ...

Did you know that most major galleries only display about a quarter of the art in their collection at one time? So what pieces of art does the gallery choose to display? And what pieces does it choose not to display?

This is something that the people at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) think about a lot.

That's why they have decided to give a modern makeover to one of their oldest exhibitions, the European collection. Unveiled March 12, the exhibit takes a different look at classic works of art—one that acknowledges issues of colonialism, racism, and gender in the art, while still letting people appreciate its beauty.

A complicated history

The AGO's European collection is found at the centre of the museum's first floor. (AGO)

For many years, the AGO's European collection has been found in a prime location on the first floor. The art shown there—from masters like Rubens, Rembrandt, Monet, Van Gogh, and Rodin—was all magnificent. It was also made almost entirely by white male artists.

Though the AGO showed lots of works by female and BIPOC artists, those tended to be on other floors, away from the heart of the gallery. This sent the message to many that these European artists belonged in this central space because they were the best there was.

In debating how to present these European works more fairly, the AGO chose to remake this central space as a place where better conversations about the art, its meaning, and its history could happen. How? Let's check it out.

Changing the words

The gallery is now using three languages in its exhibit introductions—English, French, and Anishinaabe. (AGO)

At any gallery, there are words written about the pieces of art on display or the exhibit. It gives people an idea about the history of the art and time period that it was made, as well as why all of this art is being displayed together.

Today, the AGO's exhibits now feature notes in not only English and French, but also in Anishinaabe, a language spoken by many Indigenous nations. This helps the gallery use words to highlight the complex history that helped form this art.

For example, much of the European collection was made at a time when countries like England, France, Holland, and Spain were building empires, enslaving people against their will, and gaining wealth through power. In one Dutch painting showing luxury goods from the 1700s, we see tobacco from Virginia in what is now the United States—the package's label has an image of an Indigenous person. These are riches that came from colonialism and exploiting others.

Changing what is shown

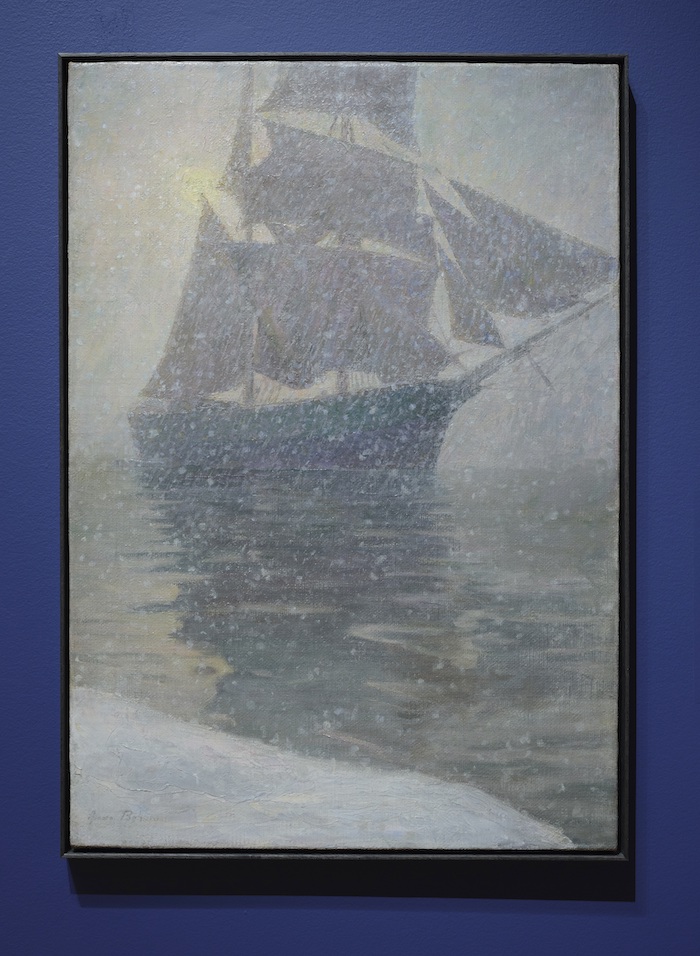

Swedish painter Anna Boberg's Sunlight And Showers is a new addition to the gallery—one of several female artists now being displayed from the time. (Anna Boberg/AGO)

The AGO also decided to change what art was displayed. Though the majority of the art is still of white Europeans and painted by white males, there are now more exceptions, which gives people a fuller picture of life at the time.

One of the new artists being displayed is Swedish painter Anna Boberg. Anna became fascinated by the far north and dedicated much of her time as a painter to depicting that part of the world. She even invented an ingenious easel that attached to her legs, allowing her to paint while in deep snow. Amazing!

Check out Anna's easel from the early 1900s! (Wikimedia Commons)

The AGO also purchased a new painting in January 2020 called Portrait Of A Lady Holding An Orange Blossom. This Dutch painting is unique in the collection because of how it shows a Black woman dressed in expensive clothing and in a confident pose. Most of the paintings of people of colour at the time—including others in the AGO's exhibit—show them serving others.

Being able to highlight this rare painting is important. It shows a version of the world that was not just about how white people saw things.

Different conversations

When the AGO bought Portrait Of A Lady Holding An Orange Blossom, no one even knew who painted it or who the woman in the painting was! Since then, they have been using research to piece together the art's important history. (Jeremias Schultz/AGO)

These are just a few examples of the many changes in the European collection. Across dozens of works of art, and many paragraphs, the AGO is trying to change how we talk about the past. And how we talk about today, too!

And speaking of other great conversations that we can have about art, check out this report we did on the work of Indigenous artist Brian Jungen from a show at the AGO in 2019.

The AGO is bringing a wider variety of artists and subjects to its European collection. (AGO)

The AGO is bringing a wider variety of artists and subjects to its European collection. (AGO)