In June we began a new series of posts designed to explore Black experiences and the problems of racism and injustice in society. We have discussed Juneteenth, John Lewis, and systemic racism, interviewed activists and educators, and even heard from readers like you!

Today we're talking about a focal point of recent protests across North America and beyond: monuments. Throughout this series, we invite the participation and feedback from readers. Thank you for joining us!

The Washington monument—like the city that it's in, Washington, D.C.—honours America's first president, George Washington. (Getty Embed)

Throughout history, wherever there have been humans, there have been monuments. From statues to monoliths to palaces, these structures can serve lots of purposes.

They can be a place of worship for a particular religion. They can be a place to remember people who have done great things—or made great sacrifices—for a society. And they can be used as reminders of horrible tragedies in our past—a marker to make sure that important lessons and stories are not forgotten.

Whatever the purpose behind a monument, all of them have an intended meaning or message—the reason why they were built. Of course, because humanity is full of different experiences and perspectives, it's hard for any monument to have the exact same meaning for everyone. And sometimes that's okay.

But what about when a monument that not only represents something completely different to a certain group, it actually represents something terrible. Something painful or oppressive.

In those cases, the question can be asked: Should that monument still exist?

The Confederate monuments

The Robert E. Lee statue as it looks today. It has been the site of many protests by activists looking for change. (Getty Embed)

This is the big question that many across the United States and Canada are asking right now. As protests build in both nations, the issue of removing monuments keeps coming up. In particular, Confederate monuments in the United States.

These are statues that remember generals and soldiers that fought against the northern Union in the American Civil War. To some people in the southern states that used to be a part of the Confederacy, these monuments help them remember ancestors who lost their lives in this horrible conflict.

But then there's the reason that the Confederacy fought the Civil War in the first place: To be able to continue the practice of slavery. That is why for Black people Confederate monuments are a painful reminder of a war fought to keep their ancestors enslaved. And why many Americans—of many different backgrounds—want these monuments removed.

And recently, numerous Confederate monuments have been removed. In addition, dozens of schools and institutions named for Confederate leaders have changed their names. And while some of these monuments still exist, the pressure to also remove them is mounting.

An expanding view

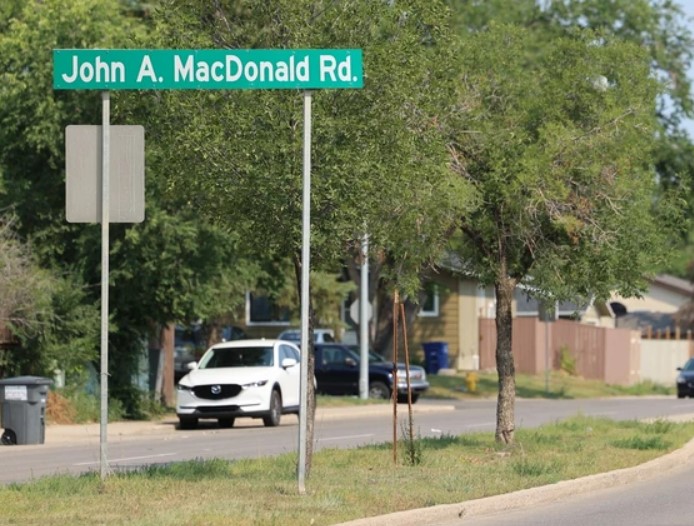

A statue of Sir. John A. MacDonald, Canada's first prime minister, in Toronto. (Getty Embed)

But now this mounting pressure is no longer just on Confederate statues. Some people also want society to acknowledge how other monuments serve as similar reminders of oppression and injustice.

For example, many early American presidents—from George Washington to Thomas Jefferson—owned slaves. Monuments to them can also be said to represent the oppression of Black people by whites.

And then there is the question of Indigenous people. President Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830 pushed them off ancestral lands to make way for white settlers. Meanwhile in Canada, prime ministers such as Sir John A. MacDonald and Wilfrid Laurier both made decisions that stole land from and deeply damaged the way of life for Indigenous people. MacDonald's residential school system brutally separated Indigenous children from their families.

These truths are deeply painful. Much like how the Confederate statues do for Black people, images of these men remind Indigenous people how Canadian and American leaders broke treaties and ripped apart their lives.

So if Confederate monuments come down, shouldn't these ones come down as well?

A trickier question

Many see Mount Rushmore as a tribute to four of America's greatest presidents. But are there other ways that it could be viewed? (Getty Embed)

This is what makes these debates so challenging. How far should the changes proceed?

Yes, getting rid of Confederate monuments is still hotly debated. But those monuments—as well as those in favour of keeping them—are generally only found in a certain part of the country. In the United States as a whole, popular opinion is in favour of the statues being removed.

But names like Washington and MacDonald are huge parts of the culture of their entire country. All across their nations, their names and faces appear on countless monuments, schools, libraries, awards, and dollar bills.

How do you remove the monuments of people who are seen as your country's founders?

How do we remember?

The Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, Germany is an example of how Germans are trying to use public monuments to address difficulties of the past. (Getty Embed)

It's not an easy question to answer. Many people express concerns that removing monuments—of any kind—means that people are trying to erase history.

But others argue that monuments are usually not where we learn about history. Instead, such statues are about paying tribute to someone. In other words, removing a monument doesn't erase the history, it only erases the idea that that particular person is someone who should be revered, or looked up to.

An interesting example to think of here is Germany. From 1933 to 1945, Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party established one of history's deadliest regimes, responsible for some of the worst crimes the world has ever seen. How does that nation address its role during those twelve years?

Germans responded by creating a movement called vergangenheitsbewältigung, which means 'working through the past'. Not only are there no Nazi monuments in the country, they have also made it a part of their education system to analyze, understand, and learn to live with their complicated past.

They do not try to glorify it. But they do not ignore it either.

Moving forward

A defaced statue of Egerton Ryerson in Toronto, Canada. Ryerson helped found Ontario's school system and has a university named for him. He also helped start the residential school system, which split and devastated countless Indigenous families. (Getty Embed)

In the end, this debate brings up this important question for Canadians and Americans to ask themselves: How do we work through our own complicated past?

Because it is a complicated past. The histories of these two countries are a mix of huge triumphs—in personal freedoms, rights, and democracy—and great atrocities, especially toward Black and Indigenous communities. To ignore one of these things at the expense of the other will always be a problem. But so is changing nothing at all.

In our interview with educator Alicia Dyson two weeks ago, she mentioned the importance of having "courageous conversations" about racism. Working through our past is an example of one of those talks.

OWLconnected will be taking a break from this series for the month August. But we're excited to launch even further into topics of social justice on this website in September. We're looking forward to it!

We want to hear from YOU! Do you have a question on this topic that you'd like answered? Do you have a message of hope or support that you'd like to express? Write us at owl@owlkids.com with the subject 'Speak Up!' and join the conversation of change.

The Robert E. Lee Memorial monument in Richmond, Virginia. In 1869, the Confederate general famously wrote of Civil War memorials "I think it wiser not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife." (Mtdozier23/Dreamstime)

The Robert E. Lee Memorial monument in Richmond, Virginia. In 1869, the Confederate general famously wrote of Civil War memorials "I think it wiser not to keep open the sores of war but to follow the examples of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife." (Mtdozier23/Dreamstime)

😀